A Brief History of Japanese American Community Cookbooks

The evolution of West Coast spiral bounds from the 1960s to the 1990s.

When I commissioned the following piece, about the cookbooks of Japanese American community centers in the 1960s-1990s, I was drawn to it as a deep-dive into a cultural group that contributed much to that beloved culinary genre, the community cookbook. Running it in the aftermath of the horrific killings in Georgia and a broader discussion of anti-Asian racism in the US, some of the themes here hit much heavier. As we tragically saw this week, the racism the authors of these books endured persists today.

Author Lola Milholland and I invite you to donate to national organization Asian Americans Advancing Justice, as well as Lola's preferred local organizations, the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon and Japanese American Museum of Oregon, both of which advocate for social justice causes impacting Asian Americans. I hope you enjoy her piece. —Paula

The moment I held the Epworth United Methodist Church Cookbook in my hands, I felt a deeply familiar comfort. Like many Japanese American community group cookbooks, it is printed in black and white on half sheets, spiral bound so you can keep your favorite recipe open, and includes line drawings and prints, in this case of Japanese family crests. These books feel lovingly handmade, but also utilitarian; they’re designed for people to cook from, not to ogle. Most are divided into the same general categories—appetizers, soups, mains, desserts—and in every case, they capture home recipes from real people in their community.

Community cookbooks aren’t unique to Japanese Americans, but over the past seventy years, Japanese American groups up and down the West Coast have been prolific, publishing cookbook after cookbook after cookbook. Most of these books were created as fundraisers by women’s groups connected to churches and temples, time capsules from the kitchens of women who gathered to carve out a space for themselves.

Yet of all the books I've read in the past year, none include narrative about who these people were, the stories behind the recipes, or even details on how the recipes should look or taste. Illustrations are often more conceptual than descriptive: a kid’s drawing of rice balls could just as easily represent sea anemones, step-by-step illustrations for how to devein shrimp include three additional shrimp floating on the page like clouds, as though deveining them freed them to fly away. Did the authors assume Japanese Americans readers would already be familiar with these recipes, and people who were not Japanese Americans would not care? Today, decades later, these cookbooks present puzzles—what is the story of these dishes, and who were their authors?

“Even though most are short on narrative, [these books] represent community history and the evolution of food from Japan through the generations in America,” Robbi Ando, who was born and raised in Oregon, tells me.

I borrowed several dozen Japanese American community cookbooks from the 1960s through the 1990s published near where I live in Portland, Oregon from women I am collaborating with on a contemporary Japanese American community cookbook. As I spent time with the books, I began to see an evolution in the authors’ perceived audience: the first books seem written for people outside of the Japanese American community, while later titles speak to the community itself, and onward to future generations.

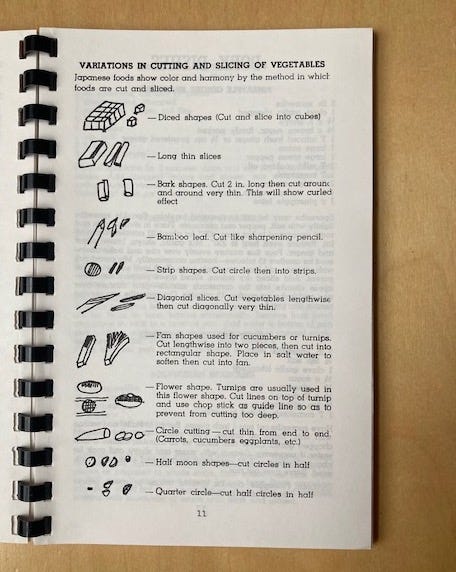

The cookbook everyone I spoke to seems to own is Oriental Recipes by the Veleda Club, first printed in 1963 in Portland, Oregon. The copy I reviewed was the 11th printing, from 1998. The writers saw their project as a form of cultural diplomacy. “Members of the Veleda Club, formed by a group of Nisei matrons of Portland, Oregon,” the book begins, “have contributed the following collection of authentic Oriental dishes—tried and true to the best of our knowledge—to help you seek new paths in the gourmet field.” The book includes a section on how to pronounce Japanese words, a thorough glossary, instructions on how to use chopsticks, illustrations of different ways to cut vegetables, and both English and Japanese names for their recipes. By 1963, residual racism from World War II may have abated slightly, but Japanese Americans were still frequent targets of bigotry. This cookbook was a gentle offering of friendship.

A Taste of the Orient, published in 1967 by the Nisei Women’s Society of Christian Service in Ontario, Oregon, opens: “In the past, so many people, especially our Caucasian friends, have asked for recipes of Oriental flavor. With this in mind, we wish to share this collection of favorite and often used Oriental recipes.” The book seamlessly integrates Chinese and Japanese recipes, showing a fluid understanding of these dishes within a broader category of otherness called “Oriental” that included other East Asians. None of the recipes translate ingredients or names, and yet the recipes offer hints about the improvisations and identities of the people living in that small community. One of my favorite nods to their non-Japanese American readers is a recipe for “hurry up hamburger,” which calls for cooking ground beef and onion in shoyu and MSG and serving it over hot rice. It’s a simplified recipe for beef soboro, a classic Japanese home-style dish, given a goofy American name.

At no point does the book mention why there is a Japanese Americans enclave in Ontario, a remote outpost on the Oregon-Idaho border. Two decades earlier, in 1942, a few months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, in a moment of irrational paranoia and racism, President Franklin D. Roosevelt hastily signed Executive Order 9066. The order sent around 112,000 U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry in the West to concentration camps in remote locales. Around 33,000 did seasonal or annual farm labor, including some who were relocated to farm labor camps very near Ontario, Oregon, where they cultivated sugar beets that were converted to industrial alcohol used to manufacture synthetic rubber and munitions. A Taste of the Orient was written by Japanese Americans who stayed in the area after the war ended.

Over the years, the idea of writing a cookbook for a non-Japanese American audience began to change. The previously-mentioned Epworth United Methodist Church Cookbook, published in Portland, Oregon in the 1990s (specific year unknown), includes a mishmash of Americana recipes (Italian Chicken in Envelopes, Coleslaw Extraordinary) and Japanese American ones (Inari-Zushi, Chawan Mushi), likely what the Japanese American community was really eating at that time. What serves as an introductory essay is a detailed explanation about Japanese family crests (mon), of more interest to the Japanese Americans who might have a connection to these crests than others. There is even less description of ingredients than in past works. A recipe for salmon eggs with sake-no-kasu never explains what sake-no-kasu, a byproduct of making sake, is, nor where to get it. This was a book by and for the community.

“There’s a lot of family ties in there,” Marcia Hara, a professional chef turned high school culinary teacher, told me. “Two people interviewed my grandmother and recorded her ohagi recipe and an uncle did the artwork… As I got older, I liked these books because I was familiar with the churches and some of the people who were members. It was a vicarious way of feeling connected.”

Sharing Our Celebrations of Life: A cookbook of family favorites recipes explicitly states its intention to create a useful guide for the next generation: “May our future generations continue to share and enjoy the cooking traditions of our cultural heritage which were passed down to us.” Compiled by the members and friends of the Idaho-Oregon Buddhist Temple and published in 1994, this book comes from the same Japanese American community that stayed in rural Ontario, Oregon after World War II that published A Taste of the Orient, nearly 30 years later. Sharing Our Celebrations of Life, more than others, includes a lot of Americana: Tortilla appetizer, Evelyn’s Bacon Tater Bites, a pretzel salad. Interspersed seamlessly are Japanese American dishes, including a chicken maze gohan which calls for konnyaku (yam cake), a very traditionally Japanese ingredient. A grandchild would be able to find his grandmother’s best chocolate chip cookies, tsukemono pickles, and also complex masago yose (a many-ingredient terrine), all in one volume.

Whoever the intended audience may have been when the books were first written, today, these cookbooks serve as a connection to Japanese American heritage. In a conversation with the publication Nichibei, Nina Ichikawa, executive director of the Berkeley Food Institute at UC Berkeley, said, “Our recipes reflect whom we loved and worked with, where we lived, when and which incarceration camp we were in, and so many other historical twists and turns. I’m not so interested in ‘purebred Japanese cooking,’ whatever that is, because that would strip our rich history away.” My friend Robbi gave a personal take on that sentiment when she told me, “While my mother gave all her daughters wonderful taste buds and was an excellent family and community cook, she never had recipes for her personal dishes and really didn’t teach her daughters how to cook. We were relegated to chopping or slicing vegetables and washing rice. The community cookbooks are first of all wishes to recreate childhood dishes.”

As I spent time with these books, I came upon some recipes over and over again. I took snapshots of four recipes for sekihan—sticky rice with azuki beans—because I want to make it so badly. But one recipe I had never heard of popped up repeatedly: variations on “mar-far” or “mah fry” chicken. Because these books have no recipe descriptions, I tried to imagine this dish from the recipe steps. The specifics change from book to book, but the overall recipe is the same: break down a whole chicken, remove the bones, and cut the meat into bite-sized pieces. Then, season the chicken pieces with funyu (fermented tofu cubes) and other flavorings, batter, and deep fry them.

This is clearly a take on a Chinese recipe that builds on a flavor base of fermented tofu, a very uncommon ingredient in Japanese cooking. What would this dish taste like? Funky? Umami-rich? It’s obviously beloved or it wouldn’t have withstood several decades of cookbook publishing. Robbi mentioned it was even served at this past spring’s Oregon Buddhist Temple fundraiser. But how did this Chinese recipe find its way into Japanese American community cookbooks, and indeed community life?

Mysteriously, the recipe didn’t appear in any of the Washington, California or Hawaii books I perused. I wondered, is this a special recipe of Oregon? When I asked Robbi, she told me, “It’s actually a Cantonese dish, Mar Far Guy. It is much like karaage [Japanese fried chicken]. At least in Portland when I was growing up, special occasions like funerals, anniversaries, and major birthdays were celebrated at Chinese restaurants with large banquet rooms. I suspect Mar Far is one of those crossover dishes, rather like JA chow mein, which I’m told does not exist in Japan.”

A Reddit post and an answers.com post combined to give more context: a chef at Kim’s Chinese restaurant in Medford, Oregon started making Mar Far chicken in the 1950s, and it became popular among Oregon’s Chinese and Japanese American populations. It’s inclusion in book after book hints at how cultures influence one another and local cuisine evolves. A dish translated from Cantonese cuisine by a Chinese cook in rural southern Oregon, then translated by Japanese American home cooks around the state, then continually adapted and preserved in these cookbooks. A recipe floating in space like a balloon, further and further from its origins and context as every decade passes. These cookbooks contain so many untethered balloons—puzzles yet to solve—and no time like the present.

Lola Milholland runs a noodle business in Portland, Oregon called Umi Organic. You can read her writing in her weekly newsletter, Group Living. She is currently working with the Japanese American Museum of Oregon and a committee of a dozen Japanese American women on a contemporary Japanese American community cookbook that will be filled with context, history, and personality.