A Brief History of Korean Cookbooks in America

Korean cookbooks are enjoying a burst of popularity. How did we get here?

Howdy cookbook fans!

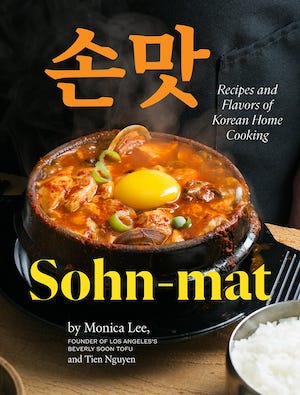

And welcome to an exciting offering from journalist Helin Jung! Helin has written a lovely exploration of the history of Korean cookbooks in the US, which have seen an explosion in popularity over the years. But they took awhile to catch on, for a lot of reasons, which Helin lays out below. It’s a dense, smart, spectacular read that starts with a racist accounting of “Queer Korean Food” from 1904 and ends looking with hopeful eyes towards the upcoming, highly anticipated Sohn-Mat by Monica Lee, former-owner of the beloved, shuttered Koreatown staple Beverly Soon Tofu, written with Tien Nguyen. I hope you enjoy it as much as I do.

Here’s Helin.

A Brief History of Korean Cookbooks in America

—Helin Jung

Korean Food Gets a Rough Start in the US

In 1904, a wire story headlined "Queer Korean Food" circulated in newspapers from West Virginia to Kansas. A year earlier, the first Korean immigrants to Hawaii had arrived to work the sugar plantations. The Korean population in the United States only numbered in the thousands. This unbylined newspaper bulletin described the Korean diet:

The Korean is omnivorous. Birds of the air, beasts of the field, and fish from the sea—nothing comes amiss to his palate. Dog meat is in great request at certain seasons, pork and beef with the blood undrained from the carcass; fowls and game—birds cooked with the lights, giblets, heads, and claws intact; fish, sundried and highly malodorous—all are acceptable to him. Cooking is not always necessary; a species of small fish is preferred raw, dipped into some piquant sauce. Other dainties are dried seaweed, shrimps, vermicelli, pine seeds, lily bulbs and all vegetables and cereals. Their excesses make the Korean martyrs to indigestion.

Korea, which had been open to trade for a single generation, was unknown to Americans. News from the Hermit Kingdom arrived via travelogues from Christian missionaries like Ethel E. Kestler, who often mentioned being so revolted that they refused to eat. (At a table laden with 18 different bowls of the "choicest Korean food," Kestler wrote in a letter that ran on the front page of The Monroe Journal in 1906, but "not appetizing in either odor or looks," "I did not have sufficient curiosity to investigate to find out.")

Prejudice is a natural response when faced with the unfamiliar. Disgust catches easily. They said the food stank, made you sick to your stomach. Who would ever want to eat like a Korean?

By 1933, a young scholar named George Kwon felt hopeful enough to publish Oriental Culinary Art, "an authentic book of recipes from China, Korea, Japan and the Philippines." Along with his UCLA classmate Pacifico Magpiong, Kwon wrote what is believed to be the first cookbook in the United States to feature Korean and Filipino recipes.

Who is a cookbook for? In this case, "housewives other than Orientals." Like other so-called Oriental cookbooks from the 20th century, Oriental Culinary Art packaged several culinary traditions from across Asia together, including dishes like chop suey that were developed primarily in America. Chinese food was already well-known among non-Chinese Americans, Japanese food was becoming more familiar, and the authors appear to have made a pragmatic choice about how best to present the strange. As Lisa Heldke writes in Exotic Appetites, "We like our exoticism somewhat familiar, recognizable, controllable. It needs to fit into some known category for us before we can even be fascinated by it." Boost the new stuff, but don't oversell it.

Korea was under Japanese rule from 1910 to 1945, the year that Harriett Morris, an entrepreneurial missionary from Wichita, self-published Korean Cooking, the first cookbook solely devoted to Korean cuisine to be printed in the United States. (The book would later be republished by the Charles E. Tuttle Company in 1959 as The Art of Korean Cooking.) Morris embraced Korea's cuisine from her position as benevolent interventionist—she helped create the Home Economics department at Ewha Womans University in Seoul—and there was no question in her mind that she should be the one to promote it. "Korean food is different from Chinese or Japanese food," she wrote in 1978, "so I decided the world should know about it."

Morris collected recipes while in Korea, then tested them upon returning to Kansas, minimizing or even omitting "some of the seasonings…in order to be more pleasing to the American taste." The recipe for cucumber keem-chee calls for half a clove of garlic and half a teaspoon of chopped red chile pepper for three large cucumbers. Ever the proselytizer, Morris saw the book as an introduction, and she took an accommodating, less "highly seasoned" route for her intended audience.

(Some) American G.I.s Develop a Taste for “Kim Chee”

Earnest though Morris's efforts were, they were swamped by the impact of the Korean War, which began in 1950 and involved nearly 6 million Americans, many of whom had little positive to say about Korean food. When Morris promoted her book by suggesting that returning G.I.s would crave the food they'd had while stationed in Korea, she was mocked in the Hartford Courant by someone who had never tasted kimchi before but had heard of that "wicked-sounding mixture."

The relentlessly bad PR went on for decades. Kimchi was "akin to murder." Raw sewage ran through the water. Can you believe Koreans eat dog meat? "In looking at Korean food an American wonders how people can eat such stuff," wrote a sergeant named Kenneth Stafford in a newspaper account about his time in Korea. M*A*S*H, which aired 256 episodes between 1972 and 1983, once featured Alan Alda's Hawkeye (one of "the good guys") eating food prepared by Koreans and saying that it was so spicy "the baby is going to need asbestos diapers."

Despite all of this, there was some accuracy to Morris’ prediction about those G.I. cravings. "Whenever men who had been in the military came into my mother's restaurant, they would ask if we had Kim Chee," Cora Snow told the Oregon Statesman Journal in 1979. Snow's mother was Jung Suck Choy, the Korean writer of The Art of Oriental Cooking, a cookbook of Korean, Chinese, and Japanese recipes that was published in 1964.

Going into a Korean restaurant with a hankering for kimchi is one thing. Wanting to cook it—finding it fashionable to do so—is another. If cookbooks are aspirational texts, as food historian Megan J. Elias wrote in Food on the Page, then it's unlikely you'd aspire to cook the food of a poverty-stricken, starved people from a country laid waste by war. It is the hunger of despair, not the hunger of appetite.

The Korean population in the United States prior to the Immigration Act of 1965 was marginal, but the three decades after 1965 saw tens of thousands of Korean immigrants arriving each year. In addition to those arrivals, over a 50-year period following the Korean War, more than 100,000 South Koreans were adopted by American families. Then came more festivals, more restaurants, more markets with more ingredients, Korean-owned sandwich shops with Korean lunch specials. An exposure therapy campaign at mass scale.

Major demographic changes and Americans' increasing appetite for food of the global Other notwithstanding, Korean food failed to launch. After Judy Hyun, a white American woman championed by Craig Claiborne, put together The Korean Cookbook in 1970, the next Korean cookbook didn't come until Copeland Marks's The Korean Kitchen, published by Chronicle Books in 1993. Upon its release, a reviewer for the Los Angeles Times wrote of the "bareness of the field—no other American trade publisher now has a Korean cookbook in print."

It was not for lack of attention. Having sufficiently rebuilt itself to host an Olympic Games, South Korea welcomed the world to Seoul in 1988. In anticipation, the Boston Globe named Korean food "the hot new cuisine" for 1986; a trend forecaster claimed in 1987 that Korean would be popular with dads. But this "lustier" cuisine remained the butt of jokes about dog meat and antacids. No matter that South Koreans were by this point lovers of standard American fare like hamburgers, pizza, and doughnuts. In 1990, Korean food was "still a mystery" according to a story by Charlyne Varkonyi that first ran in The Baltimore Sun; in 2001, it was "mystifying."

So Where Were All the Korean Cookbooks?

Korean food being a closed book has something to do with the fact that Korean immigrant communities have, as a rule, been insular. As sociologist Pyong Gap Min has noted, Koreans tended to work for other Koreans, continuing to speak the Korean language and remaining socially isolated. Their children, however, expanded beyond those boundaries. This new generation spoke English, they married non-Koreans (often white Americans), and they were well assimilated. Once they came of age, they made ideal interpreters.

Still, making a Korean cookbook in English presents unique challenges. First, there's the problem of language and spelling. Romanizations of Korean can be incomprehensible and often inconsistent: Marks's book spells the Korean word for mushroom as "beuseus" and "pusud" on a single spread, for example. Both are supposed to make the same sounds, but would you know how to pronounce them? Is it better to spell it jjigae, tchigae, or chigae? It's a relief to me when a cookbook spells out the Hangul names for dishes; at least then I can know for sure what it's supposed to be.

Korean meals are also structured differently than American ones, and while there have been plenty of concessions made to globalization, the grammar of a Korean meal requires different rhythms of preparation, not all of them easy to map onto a main-and-a-side kind of meal plan. A typical Korean meal requires multiple separate components, including, but not limited to: rice, soup, and several small plates of mit banchan. Terms and categories don't translate easily across traditions.

Beyond that, there's the fear of rejection to contend with. Ambassador foods were bulgogi, bibimbap, japchae, mandu, and kimchi—the end. Koreans have resisted touting more challenging flavors for fear of shame and ridicule. Historically, they had reason for concern, but this self-censorship closed off vast swaths of the cuisine. Without exposure, the barriers to entry for non-Koreans remained high.

A New Millenium, a Turning Point, and Maangchi

Florence Fabricant of the New York Times declared that Korean food was "just waiting to be discovered" in 1999, the year after Jenny Kwak's Dok Suni cookbook came out from St. Martin's Press. Kwak was part of a young vanguard that succeeded in making Korean cooking less intimidating for a non-Korean readership, partly by writing from the point of view of Korean Americans with feet in both cultures. Kwak brought a greater degree of memoir into Dok Suni than had been present in previous Korean cookbooks, and two subsequent Korean cookbooks that followed, Hi Soo Shin Hepinstall's Growing Up in a Korean Kitchen (2001) and Cecilia Hae-Jin Lee's Eating Korean (2005) were similarly personal and homey in style.

Lee began writing about Korean food in the late 90s, beginning with a primer on kimchi for the Los Angeles Times. "I felt this weird compulsion," she told me, "to introduce Korean food to everyone." Forty publishers rejected her book proposal before she got to Wiley. On the book's back cover, they printed the line: "Experience the savory secrets of the 'other' Asian cuisine."

The long-awaited moment of arrival began with a new era of the Korean American chef: David Chang, Corey Lee, Roy Choi, Edward Lee, Sang Yoon. Ethnic groups take "at least three or four generations" to acquire prestige, according to food scholar Krishnendu Ray, and Koreans were on their path of ascension. Formally trained with fine dining bona fides, these male chefs were savvy marketers and exceptional communicators. They did not want to "just" be seen as Korean, but neither did they deny their Koreanness. Chang, for example, described his relationship with Korean food as “complicated” in 2016—but that didn’t stop him from putting Korean flavors and dishes like bo ssam on the menu at his restaurants. Korean food's profile began to snowball by association, even if it wasn't those chefs' express goal to make it do so.

Concurrently, the South Korean government launched a campaign in 2009 to popularize Korean cuisine worldwide, which dovetailed with the inescapable cultural imperialism of Hallyu, which has brought us everything from BTS to Parasite to Innisfree. Marja Vongerichten wrote The Kimchi Chronicles in 2011, a cookbook companion to the television series in which she explored her identity through Korean cuisine. Both the book and the series, which was supported by the South Korean campaign, featured her husband, Jean-Georges Vongerichten, but that spotlight paled in comparison to what a woman cooking in her home kitchen would soon accomplish. Yes, who would have thought: Maangchi. This undiluted ahjumma with an accent thick as my mother's showed up on YouTube to become the preeminent—should we call her an influencer? in Korean cooking. Hundreds of videos, millions of subscribers, and two cookbooks later, Maangchi, otherwise known as Emily Kim, maintains the intimacy of someone who invited you over to learn how to cook a thing for fun.

When it Rains: A Critical Mass of Korean Cookbooks

In the last decade, a canon of Korean dishes has emerged, a constructed national cuisine. The South Korean government has played a large role in the standardization, with dishes from the north either absorbed or eliminated. Cookbook writers with audiences beyond Korea have, perhaps inadvertently, promoted this generic and decontextualized list of staples. The proliferation of these recipes has also, on occasion, allowed others to bring different ideas into the fold.

The New York chef Hooni Kim was approached to write a cookbook in 2012, a year after his restaurant Danji became the first Korean restaurant in the world to earn a Michelin star. His first two manuscripts were restaurant books, but his editor, Maria Guarnaschelli, told him he needed to do better. By the time My Korea finally came out in 2020, it was in a radically changed form than where it began. In the intervening years, other Korean cookbooks (like Sohui Kim's Korean Home Cooking, now in its seventh printing, and Robin Ha's graphic cookbook, Cook Korean!) had taken on the mantle of presenting Korean food basics, and Kim could focus on "the way I look at Korean food."

Who is a cookbook for? In the case of My Korea, it was for Kim. "This was like a diary," he told me, an emotional reminder of his growth as a chef of what he romanticizes as traditional Korean cooking. Kim felt unburdened to do this thanks to other recent releases, and by the fact that he was told "the audience for Korean cookbooks was not Korean," and "ninety percent aren't going to really cook any of the dishes."

The Future of Korean Cookbooks with Sohn-Mat

According to Pew Research Center, 12 percent of restaurants in the United States serve Asian food. Of those, 71 percent serve either Chinese, Japanese, or Thai food. Korean comes in sixth. The distribution feels different in Los Angeles, where Koreatown spans three-square miles and there are hundreds of Korean restaurants to choose from. Anthony Bourdain, ever a culinary adventurer if there was one, said in an interview with Lucky Peach in 2016 that whenever he was in Los Angeles, "I go to Koreatown first, because it's a wonderland. You can drive for block after block after block, it's enormous. You can really get lost. And the Korean food is so perfect, so pristinely untouched by time."

Korean food, virginal and wild, still just waiting to be discovered. As Heldke writes, at the top of the hierarchy of exotic cuisine is the "true cuisine, unmediated by any outside influences." Here, Bourdain was boasting of having tasted it. Had he been the one to unseal the cave? Where did he get this idea that Koreatown had resisted change and influence?

One of the places Bourdain visited in 2013 for Parts Unknown was Monica Lee's Beverly Soon Tofu Restaurant. In the episode, he sits with Roy Choi, who explains that Beverly Soon Tofu, with its made-to-order, customizable menu, could have only happened in Los Angeles. Lee did not get a voice on the show, but she will in her forthcoming cookbook Sohn-Mat, the first to be written by a chef/restaurateur from Koreatown LA. (A different trailblazing book from 2009, edited by Allisa Park and called Discovering Korean Cuisine, featured recipes from several restaurants in LA's Koreatown, but it had a small run and is currently out of print.) Perhaps what Bourdain meant was that Koreatown in Los Angeles, despite having a concentration of Korean restaurants vastly superior to those anywhere else in the country, had been invisible to publishing and media outside of LA. Exotic to whom?

In truth, Lee evolved her restaurant's menu continually from when it opened in 1986 until its closure in 2020. Encounters with her customers regularly inspired new variations and new dishes. Non-Koreans started coming to Beverly Soon Tofu a few years into its opening, she said, and toward the end, most of the clientele was non-Korean, some of whom were eating the tofu soup with a spice level that was uncomfortable even for Lee to eat. Many waited hours, in tears, on the restaurant's last days for their orders. The cookbook is a gesture of thanks, as well as an acknowledgment of her own contributions to the growing understanding of what Korean food is and has the possibility to be. To know it is often to love it, as it has taken this country just over a century to find out.

Helin Jung is a writer in Los Angeles. She owns a great many cookbooks, including some she cooks from.

Fantastic article! Really enjoyed this read.

Terrific post. I learned so much! The first Korean cookbook I bought was Dok Suni. I loved the nostalgic layout, which included photos of family members. It was easy to cook from, and the recipes turned out well. I too went to Beverly Soon Tofu Restaurant after watching the Parts Unknown episode, and was distraught when the restaurant closed. Now I have a book to look forward to. Thank you for this valuable context, Helin Jung.