Inside a Legendary Designer's Recipe Sketchbook

Cipe Pineles changed magazines forever. Her illustrated recipes tell a personal tale.

Howdy cookbook fans!

A treat for you today! Designer Frances Baca is back to talk cookbook design, this time looking at 20th century magazine designer Cipe Pineles’s cookbook, Leave Me Alone With the Recipes. Pineles’s work was incredibly influential in the magazine world, and as you’ll see below, the cookbook world could learn much from her beautifully illustrated recipes.

Today I am off to beautiful Houston, Texas, where it is going to be delightfully chilly for a change and I am going to eat my way across town to celebrate my birthday. And maybe go cookbook hunting—I always have great luck at Houston used bookstores. Drop Houston recs in the comments? I have reservations for the evenings but otherwise making it up as I go along.

Okay Frances! Introduce us to Cipe Pineles and her beautiful book.

The Playful Magic of Designer Cipe Pineles’s Cookbook

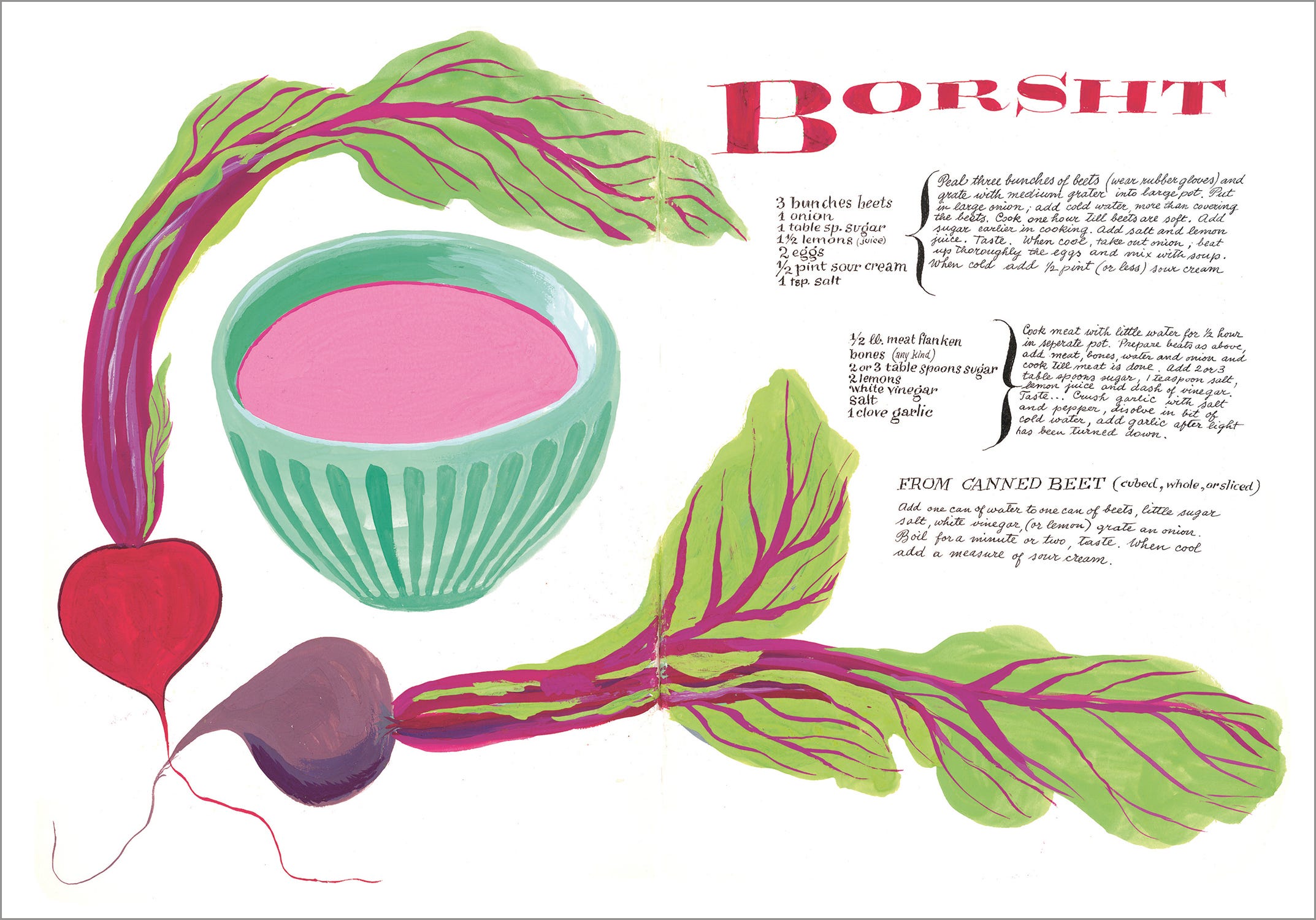

I am imagining Cipe Pineles, the pioneering yet woefully little-known twentieth-century graphic designer, seated quietly, alone, at her dining room table in New York City. The year is 1945. The sunlight from a window next to her table is streaming down onto a hardcover sketchbook that she gently opens and lays flat. She begins to recall her mother’s borscht—ruby red, flavorful, and deeply satisfying. Perhaps she closes her eyes while she savors the memory, a faint smile on her face, before she reaches for a paintbrush. Mixing a vibrant palette of gouache paints, she begins laying down color onto the pages. Once satisfied with her painting, she trades the paintbrush for a pen and begins hand-lettering instructions for making the borscht, expertly filling the space she has reserved just for this purpose. Completing her work, she sits back and admires the beautiful composition before her, breathing in a sigh of contentment.

This practice of painting and lettering seems to stop time, offering Pineles a moment of calm and focus—a brief respite from a life filled with the demands of work and family. She returns to her sketchbook again and again, continuing through the early 1950s to fill its pages with gorgeously illustrated recollections of her mother’s cooking. She called it Leave Me Alone with the Recipes, and though Pineles never completed the book in her lifetime (she passed away in 1991), its creation was a happy pursuit that memorialized the foods she grew up with.

Pineles’s sketchbook languished in the cellar of her New York home until it was purchased by a collector who undoubtedly recognized its value. Unbeknownst to either the collector or to Pineles’s family, though, it would one day find its way into the hands of modern stewards who would finally allow this very special cookbook to be appreciated by all.

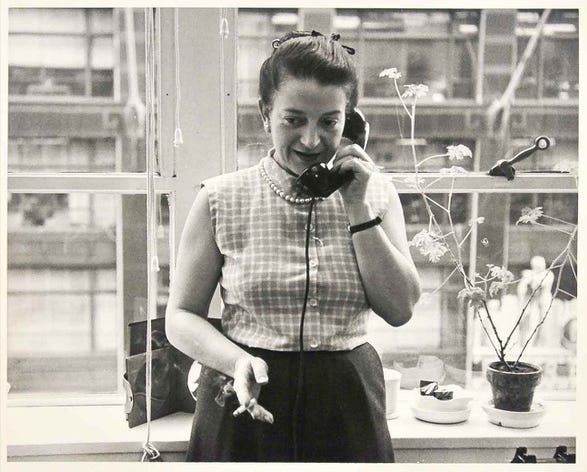

Pineles the Trailblazer

Pineles was born to Orthodox Jewish parents in 1908 in Vienna, Austria. She emigrated with her family to Brooklyn in 1923, and later studied art at the Pratt Institute in New York City. She entered the workforce at the start of the Great Depression in 1929, and eventually landed a position with a consortium of designers called Contempora, in New York City. It was at Contempora that her work designing patterns for window displays was brought to the attention of magazine publisher Condé Nast. She was hired promptly by Nast and in 1932 began working as an assistant to Dr. Mehemed Fehmy Agha, the highly regarded art director of such magazines as Vogue and Vanity Fair. Pineles was given considerable independence while working with Agha, and her creativity blossomed.

In 1942, she became art director at Glamour, making Pineles the first woman art director at an American magazine. Pineles went on to become art director for such magazines as Seventeen, Charm, and Mademoiselle. It was while at Seventeen that she pioneered the practice of hiring fine artists to create editorial illustrations—unheard of at the time but widely adopted since then.

Pineles achieved further significant milestones, becoming the first woman member of the Art Director’s Club of New York and the Alliance Graphique Internationale, two prestigious design organizations. She was inducted into the Art Director’s Club Hall of Fame in 1975, and was posthumously awarded the American Institute of Graphic Arts Medal—the “Oscar” of the graphic design world—in 1996. Despite these accolades, her work has remained sparsely documented and underrepresented in surveys of graphic design history—most certainly a circumstance of the sexism Pineles so often encountered throughout her life.

Wendy MacNaughton, a champion of illustrated cookbooks and artist of the celebrated Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, had never heard of Pineles when she came across her forgotten sketchbook. This serendipitous discovery led to an effort to bring Pineles’s name—and her cherished family recipes—back into the spotlight.

From the Cellar to the Bookshelf

On a foggy day in San Francisco in 2013, Pineles’s sketchbook sat open, under glass, on display at an antiquarian book fair. The sunny bowl of borscht she so lovingly painted seven decades earlier attracted McNaughton’s eye, who marveled at its beauty. She purchased the sketchbook together with her colleagues, writers Sarah Rich and Maria Popova, and designer Debbie Millman. They all agreed that the art demonstrated remarkable sensitivity and skill, and felt astonishingly contemporary.

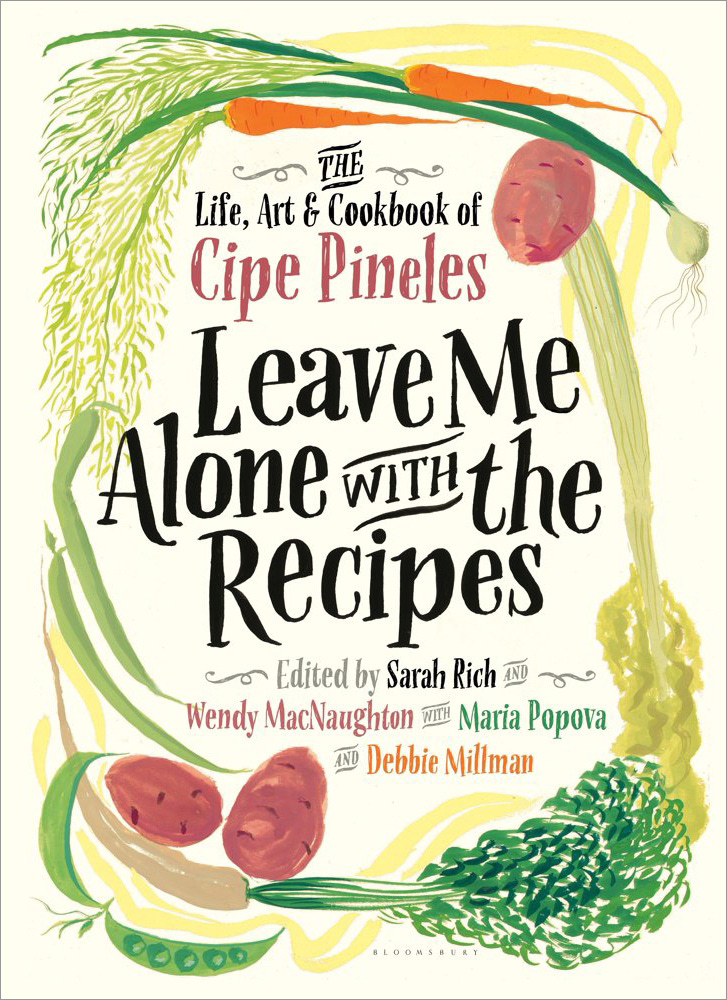

The purchase of the sketchbook initiated a quest to publish it. MacNaughton, Rich, Popova, and Millman researched Pineles, conducted interviews with her family and friends, and commissioned essays on her from authorities in the fields of both design and cooking. Rich tested and fine-tuned the recipes, and together with San Francisco chef Christian Reynoso, created an additional set of updated recipes that reflect modern tastes and ingredients. Designer Roberto de Vicq—who coincidentally worked at Condé Nast early in his career—was tasked with unifying the art with the essays and updated recipes into a new book, honoring Pineles’s dynamic and joyful style.

In 2017, the new material was published by Bloomsbury along with Pineles’s original art. Leave Me Alone with the Recipes was, at long last, seeing the light of day.

Made With Love

In her art for Leave Me Alone with the Recipes, Pineles infused a vibrant new spirit into her mother’s Old-World recipes. These foods, that in postwar America were seen as old-fashioned and unglamorous, suddenly felt fresh and modern. Pineles’s daughter, Carol Burtin Fripp, believes that her mother began the paintings to celebrate her Eastern European Jewish heritage and the traditional foods she grew up with. Perhaps Pineles saw the art as a way to honor her mother, whom she credits as the author of the recipes. Or perhaps creating the art was simply an enjoyable activity. Pineles was a prolific artist and an avid cook who took great pleasure in both pursuits.

The timing of the sketchbook’s creation may hold some key to its inspiration, as Pineles began working on it at the end of World War II in 1945, shortly after returning to New York from a brief stint in Paris as a creative advisor on Overseas Woman magazine. Though she never spoke of them, the horrors of the Holocaust—so close to the places she lived as a child—may have moved her to reclaim the beauty of Jewish traditions in the face of such atrocities. Pineles’s son-in-law, Robert Fripp, recalls her telling stories of rationing and scarcity in Paris, and her gratitude for the safety and prosperity of life back in New York. Pineles held dear the abundance of her family kitchen and the connections forged among her loved ones through food.

The sketchbook contains about twenty-five complete recipes with art, and several pages with paintings but no recipes. Though she more than likely intended to continue working on it—mentioning the sketchbook often to her family—it got lost in the shuffle of Pineles’s busy life and the upheaval of a move from New York City to the suburbs in 1955. The sketchbook’s meticulous layout suggests that Pineles intended to publish it, or at the very least, reproduce the art in other ways.

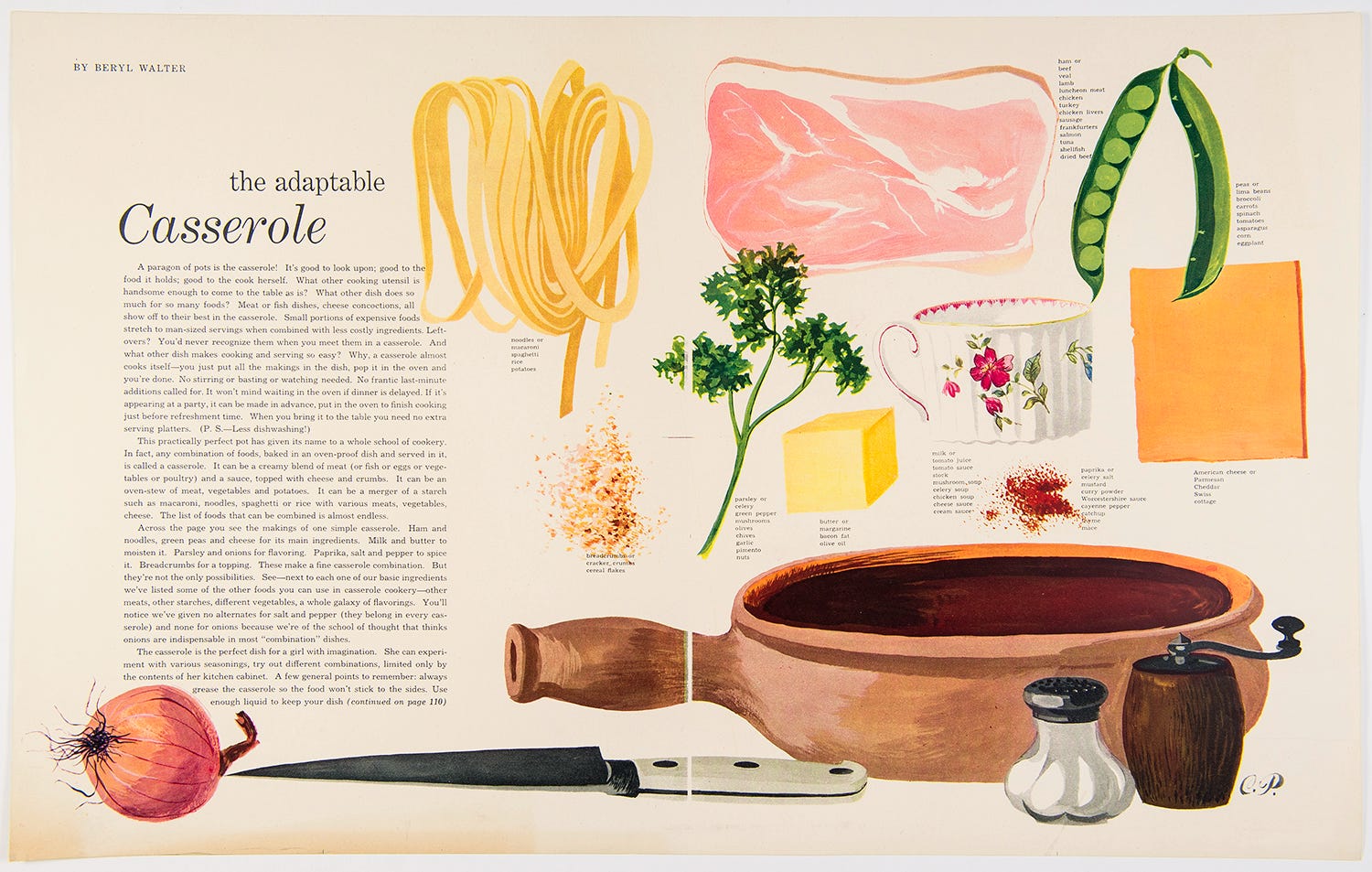

The following few spreads from Leave Me Alone with the Recipes highlight Pineles’s talent, and are full-size direct reproductions of her original art. In most cases, we never see cooked and plated food on any of the pages—a stark contrast to the very literal depictions of finished dishes we are accustomed to seeing in contemporary cookbooks. Pineles instead presents us with art that conveys the spirit of the recipes: bountiful mounds of produce, patterned fabrics and surfaces, family portraits, and colorful pots and pans. The immediacy of her art makes the food feel enticing on a more emotional level—we can sense her joy in creating it, as well as the unabashed affection she has for the recipes and the family from which they came. Noting this quality in Pineles’s sketchbook, MacNaughton remarks, “Just as when people say you can taste when food was made with love, you can also see when a drawing was made with love.”

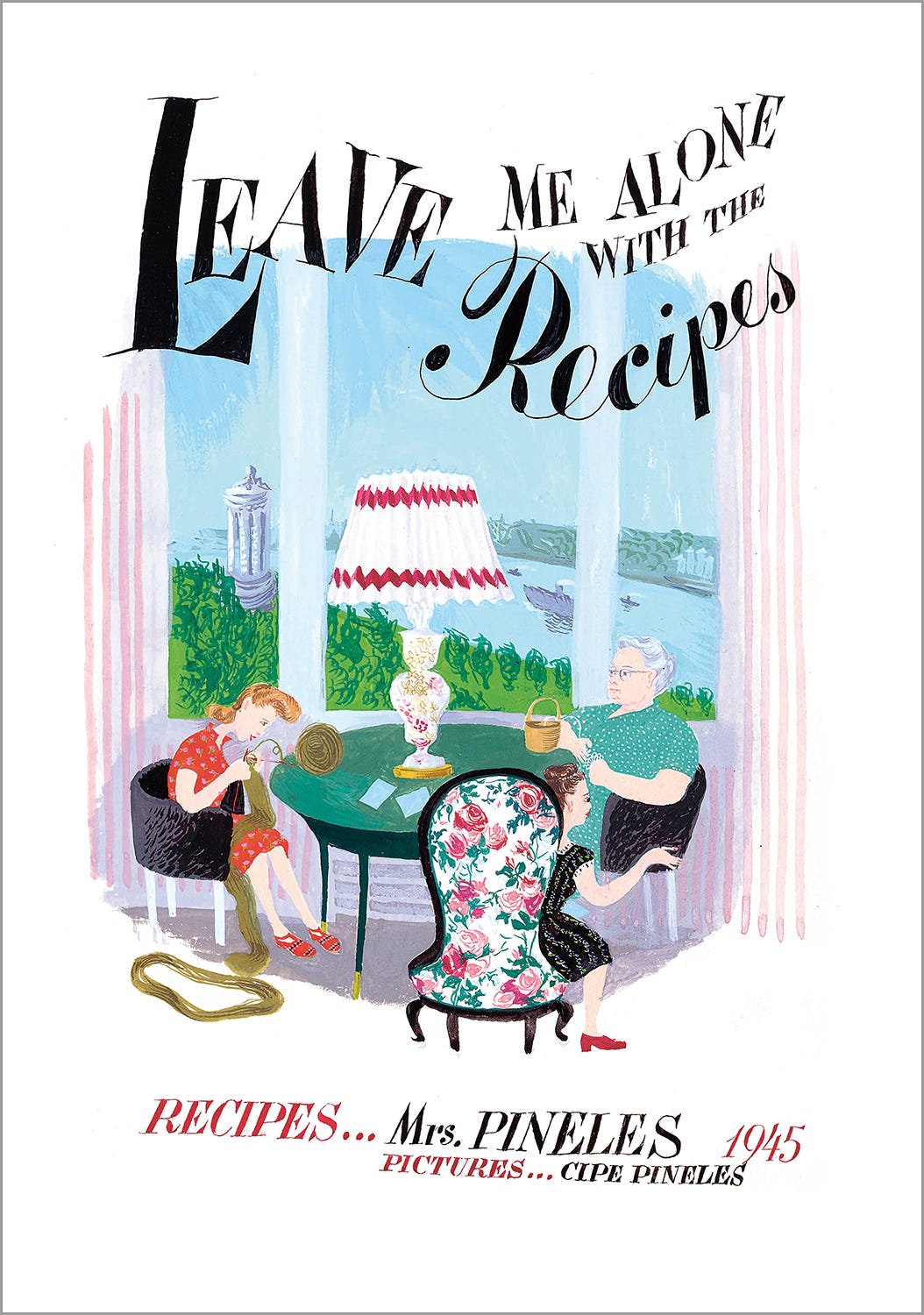

Cover

Pineles’s mother, Bertha, is featured in much of the art, including the cover. Here, she knits with her daughters Regine and Debora, Pineles’s sisters, with an impressive view of the Hudson River over her shoulder. Note the elaborate floral pattern on the chair and the enormous lamp—Pineles loved decorative detail and, over the years, reproduced in her art many of the items in her home.

The origin of the title “Leave Me Alone with the Recipes” is unknown, but thought to either indicate Pineles’s desire to lose herself in cooking and painting, or to indicate her mother’s annoyance, who was made to measure and explain recipes she was accustomed to cooking without interruption

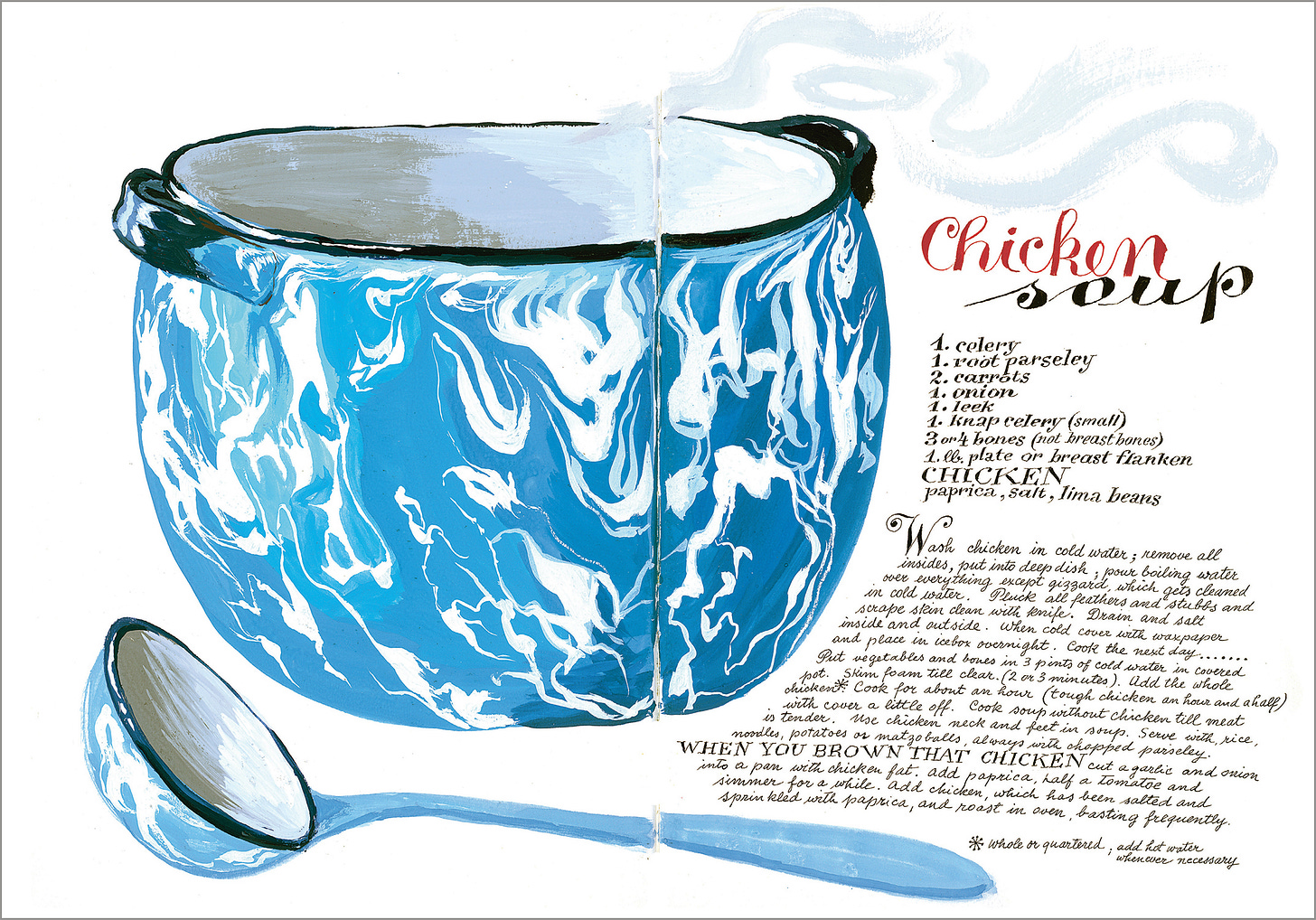

Chicken Soup

A lovely blue pot and ladle from Pineles’s kitchen provide a bold focal point for this composition. The soup—whose steamy goodness wafts into the letters “S-O-U-P”—feels appetizing and comforting, without even showing us a drop. Rich notes that the short rib bone (or “flanken,” when purchased from a Kosher butcher) that the recipe calls for is a revelation, deliciously enriching the broth.

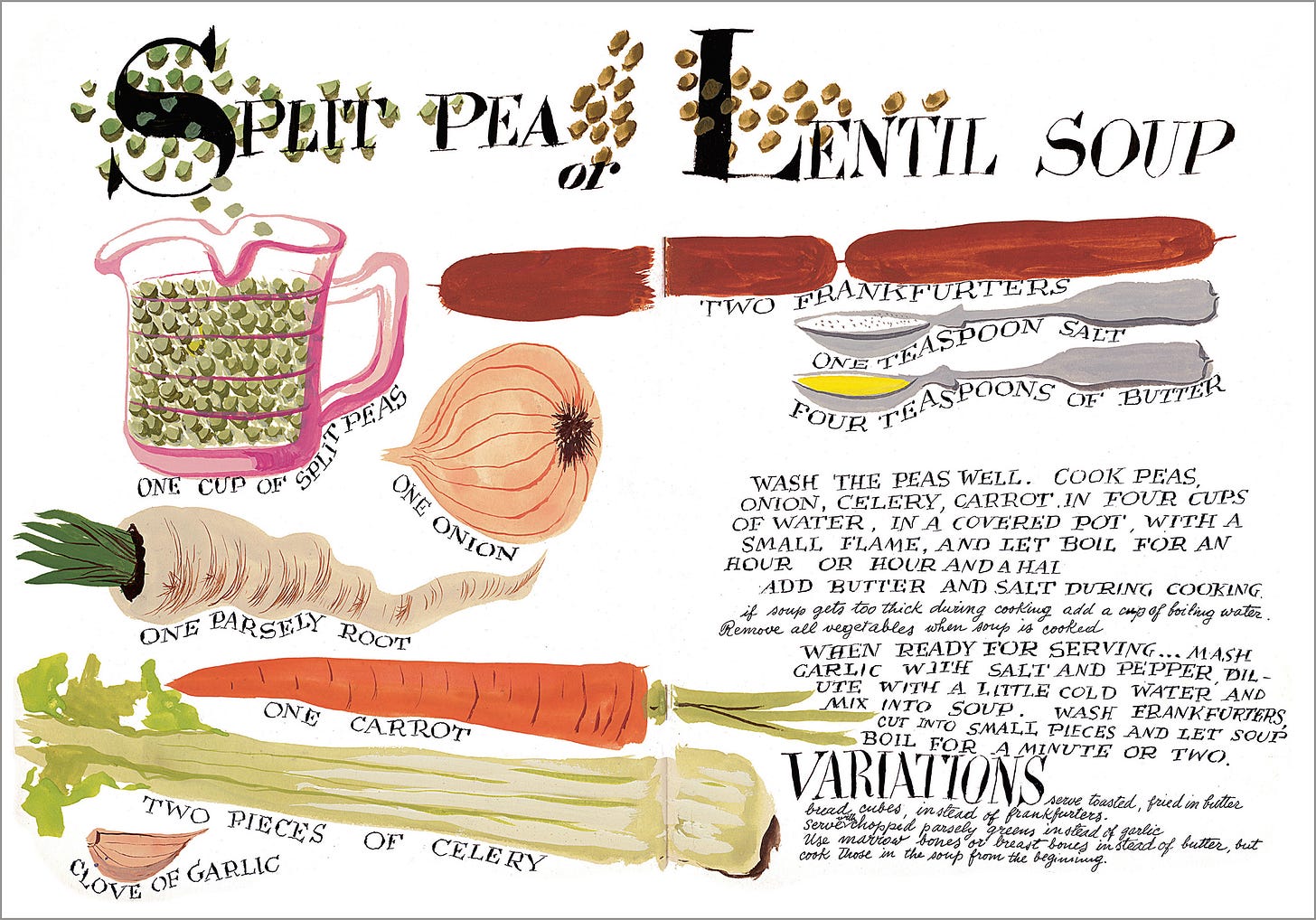

Split Pea or Lentil Soup

This recipe functions almost like an infographic. Pineles provides not only an image of every ingredient, but also shows exactly how much of each is called for. The split peas and lentils spill over the title, playfully creating a sense of depth. Her love of typefaces such as Didot is evident here, as she mimics its extreme contrasts between thick and thin strokes in her delightfully imperfect hand-drawn type. Tiny quirks like inserting “with” (third line from bottom) enhance the appeal of the art.

Rich notes that this recipe is one of the few whose ingredients and preparation are more mid-century American versus Old-World European, perhaps an indication that it was created by Pineles.

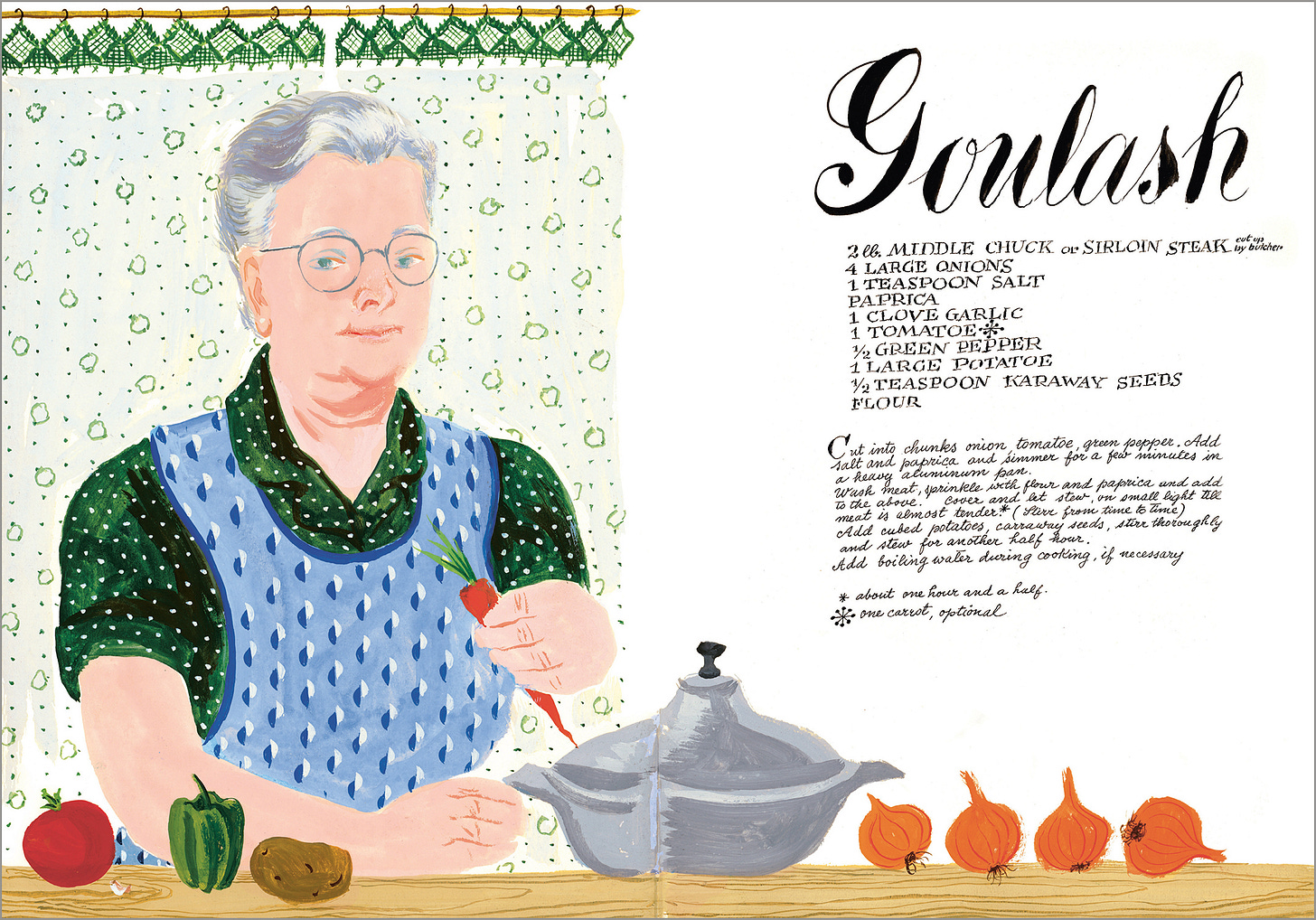

Goulash

Mrs. Bertha Pineles appears, once again—this time gazing out at us as she prepares goulash. The softness of Mrs. Pineles’s features portrays a woman comfortable in the kitchen, and maybe a bit bemused by her daughter’s interest in painting her portrait. Note what appear to be European lace curtains behind Mrs. Pineles, and her carefully detailed dress and apron. This love of pattern may be a holdover from Pineles’s days designing for Contempora.

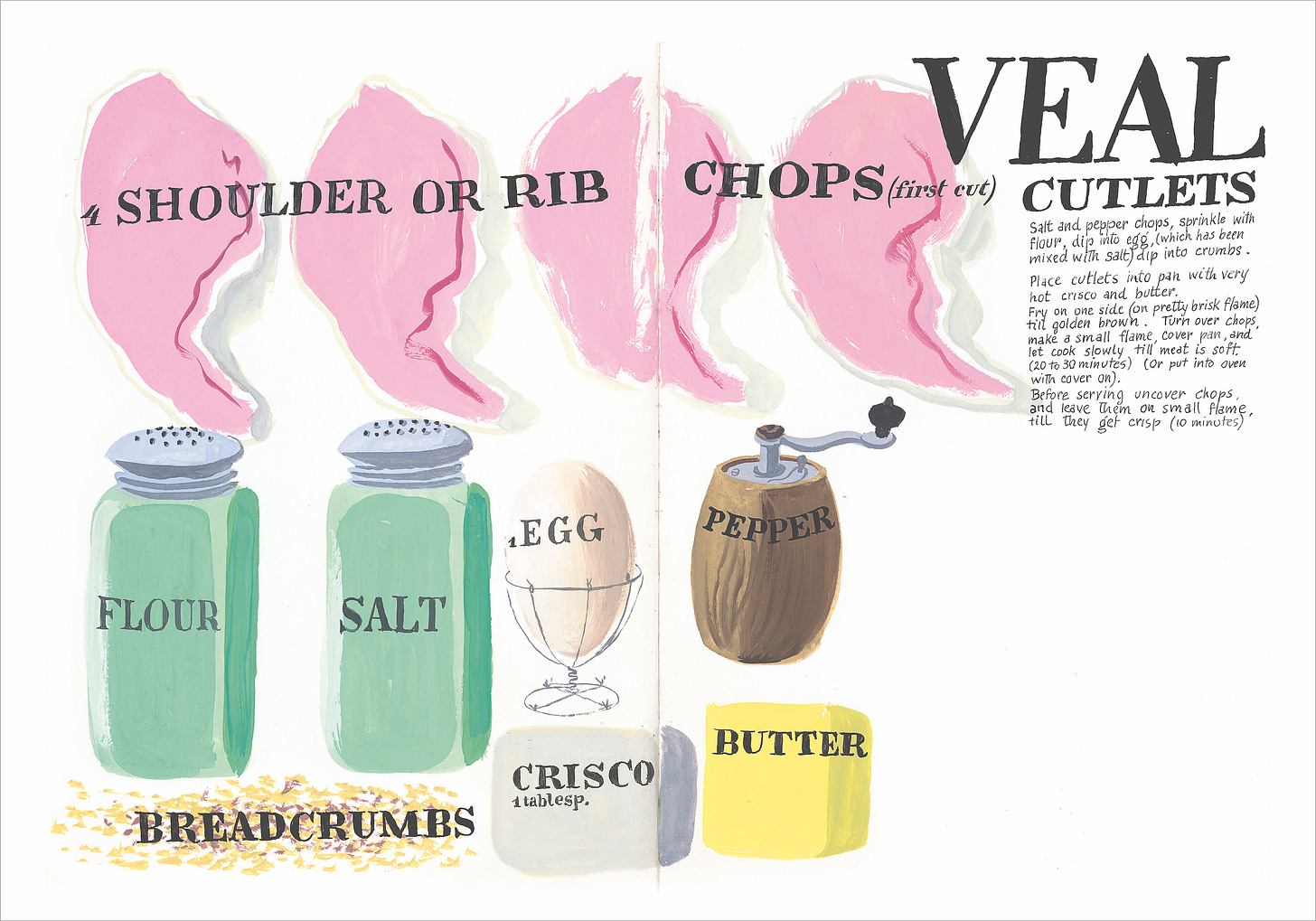

Veal Cutlets

The recipe for veal cutlets presents another visual inventory of ingredients, this time with bold hand-drawn type set on top. The recipe method is rendered in a more casually drawn script that resembles a rounded sans-serif typeface.

Curiously, there is a large empty space at the bottom right-hand corner of the art that seems to beg for a plate of prepared cutlets. Perhaps Pineles was planning to return to this, as her attentive designer’s eye would surely not allow for the final composition to feel unbalanced or incomplete. A few other spreads in her notebook also have large open fields that seem to have been reserved for more art—hinting that she likely bounced back and forth between recipes as she painted.

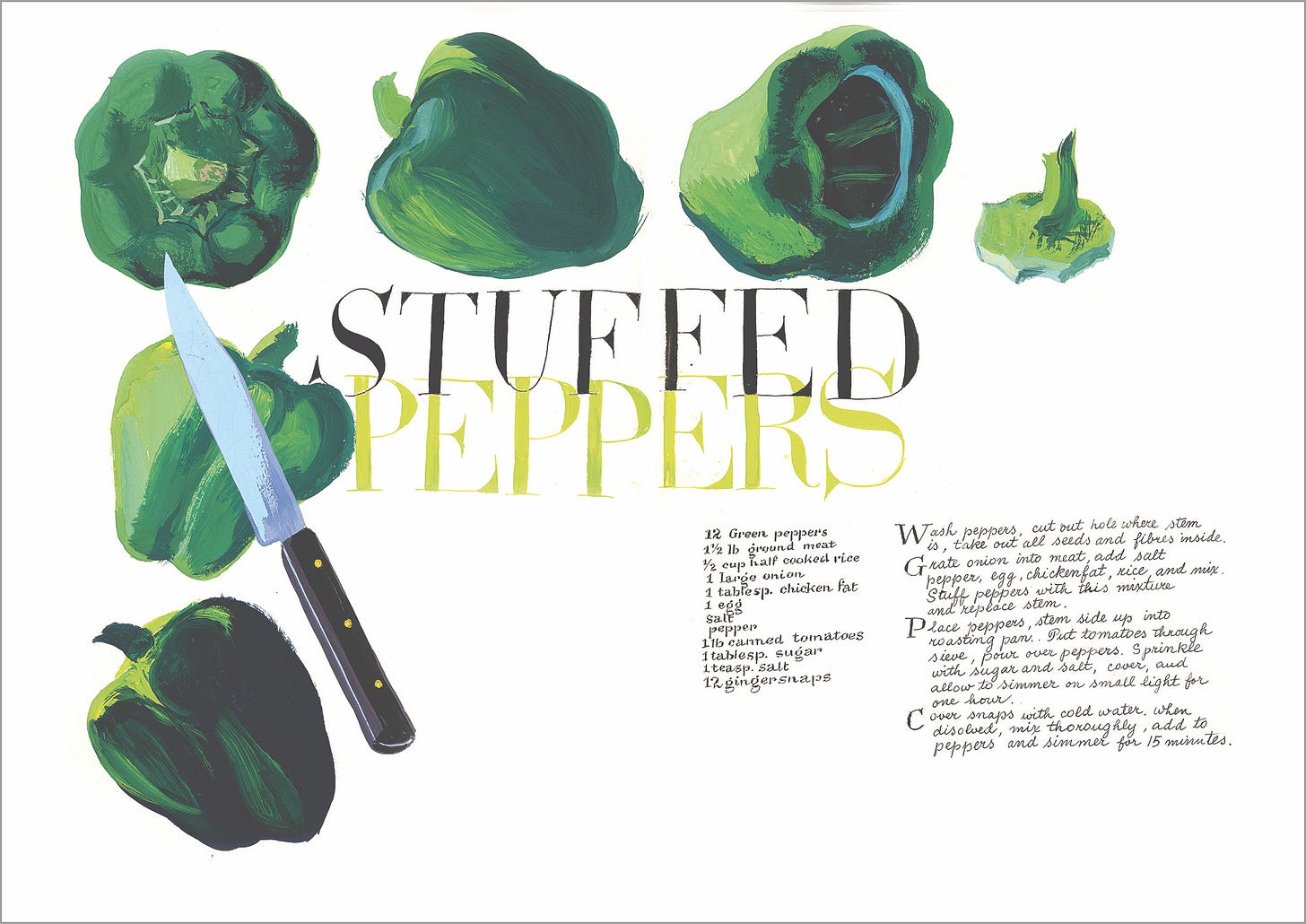

Stuffed Peppers

This recipe for stuffed peppers displays a couple of fun typographic treatments. The overlapping “Stuffed” and “Peppers” creates a sense of depth, and the hanging drop caps in the method (“W,” “G,” “P,” “C”) is a device that feels lifted straight from the pages of a magazine.

I particularly like the way the peppers are shown at different angles, almost like she is showing us one pepper that is turning toward the method, its gaping mouth waiting to be filled. Notice the way she positions the knife upward—leading our eyes up and around, and creating a sense of safety as the blade points away from the bottom right-hand corner of the page where our attention will ultimately linger.

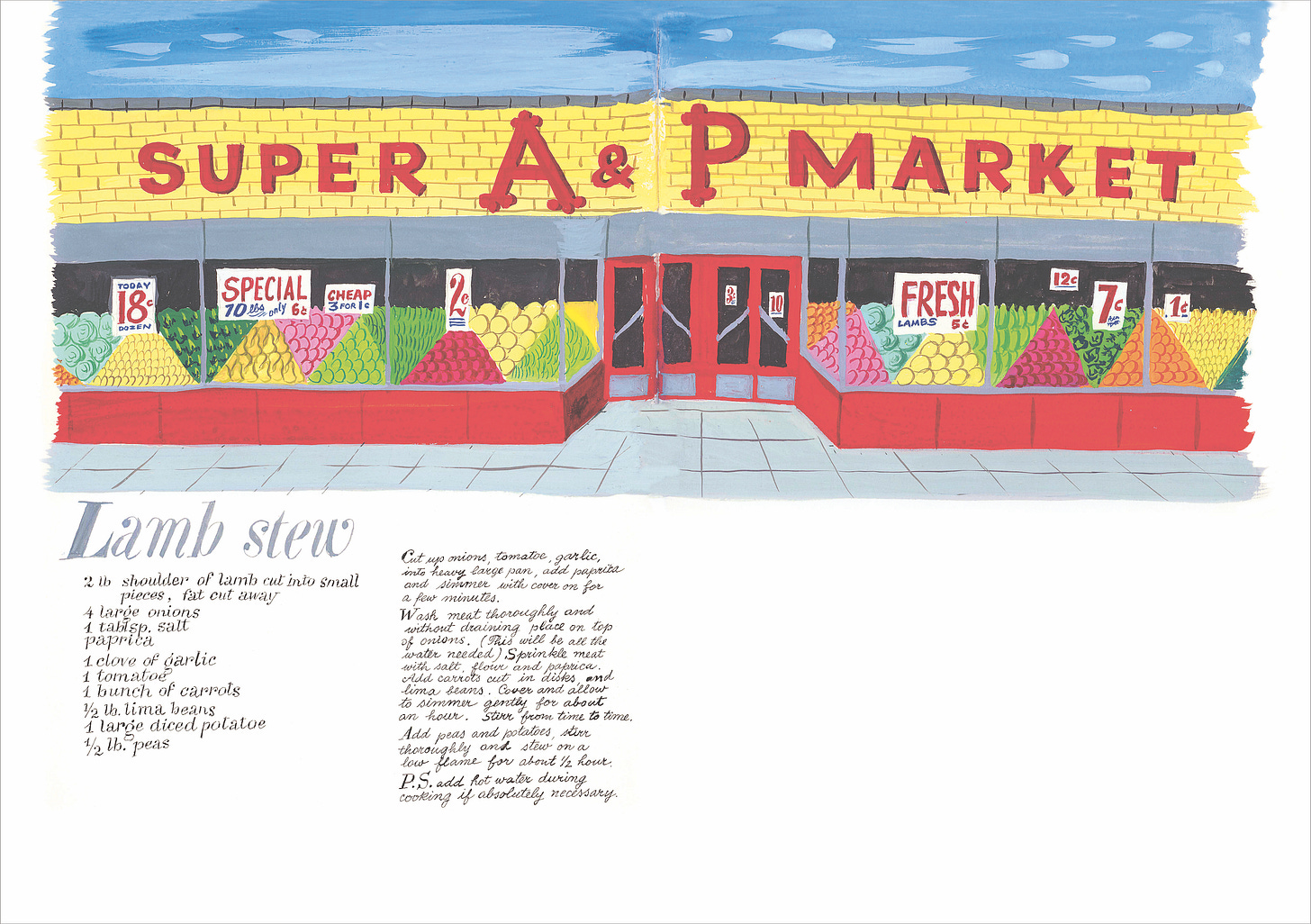

Lamb Stew

Pineles employs the element of surprise here, as she presents us not with a steaming bowl of lamb stew, but instead takes us shopping—depicting a part of the cooking process that is rarely imagined or described in a recipe. And who could resist this store? Bright and inviting, with plentiful produce arranged in colorful, neat pyramids. This may have been her local A&P or just an idealized version of one, but it clearly speaks to the bounty of mid-century America.

Again, we see a large empty field at the lower right-hand page. Maybe this space was reserved for a shopping bag with the ingredients spilling out, or an empty bowl or two, waiting to be filled? Robert Fripp speculates that these white spaces may be the influence of a more minimal Swiss design aesthetic—though my designer’s instinct says otherwise, especially given the exuberance of Pineles’s more complete paintings. It’s possible she simply got distracted. “But that’s Cipe—maybe the phone rang!” laughs Fripp.

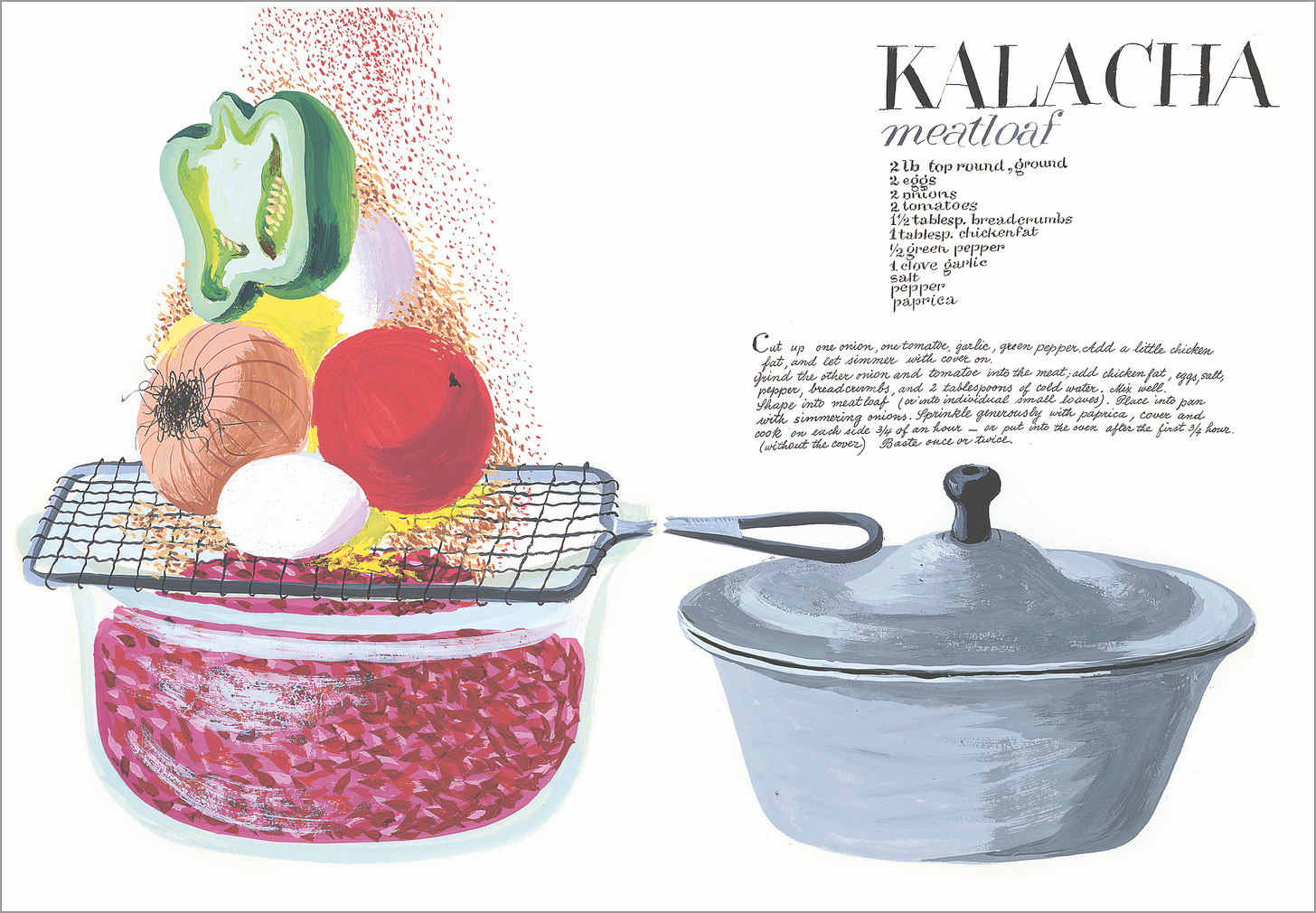

Kalacha Meatloaf

The theatricality of this composition is wonderful. The jaunty pyramid of vegetables and ground beef, sprinkled with a gentle rain of fiery red paprika, feels so inviting—even the yellow blob that appears to be chicken fat behind the onion looks appetizing. These bold shapes and colors contrast starkly with the sober gray Dutch oven at right, providing us a place to rest our eyes from the jubilation of the opposite page.

Rich notes that Pineles’s recipes were not thoroughly tested and may not result as expected. This one, for example, produced something more like a delicious Bolognese versus a firm meatloaf. Please refer to the updated versions of the recipes on pages 88–127 of the published book if you’d like to try any of these at home.

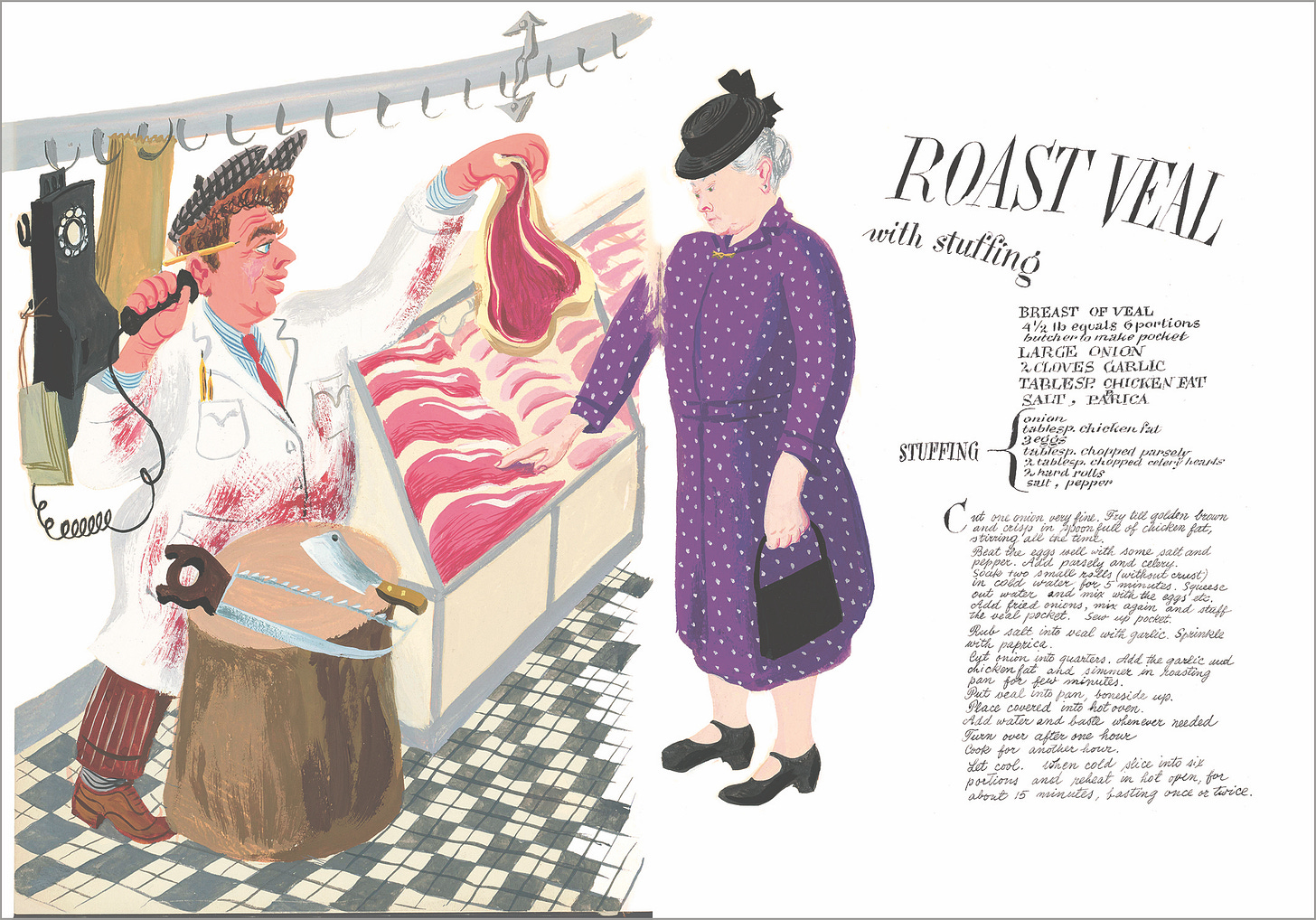

Roast Veal with Stuffing

In this delightful and humorous painting, Pineles subverts our expectations by presenting a scene from the butcher shop versus an enticing platter of roast veal. Mrs. Pineles is, once again, featured in the art, pointing with calm authority at her selection in the meat case. The butcher—who was indeed the family’s local butcher and whose likeness Pineles painted here—has one hand on the phone and the other one dangling a fresh slice of veal in Mrs. Pineles’s direction.

Pineles frequently shopped with her mother, and surely no detail of this space escaped her sharp eye. The colors, patterns, and shapes that we see here are marvelous—from the spotted purple dress and matching black hat, purse, and shoes to the checkered floor tiles to the rather brutal-looking saw to the bloodied butcher’s apron, sharpened pencils at the ready in the breast pocket. Another tiny detail: the added “P” in “Paprica” (line 7 in the ingredients list). Pineles’s recipes are not without misspellings nor errors in rendering the type, which attest to the casual and rather fluid nature of her work.

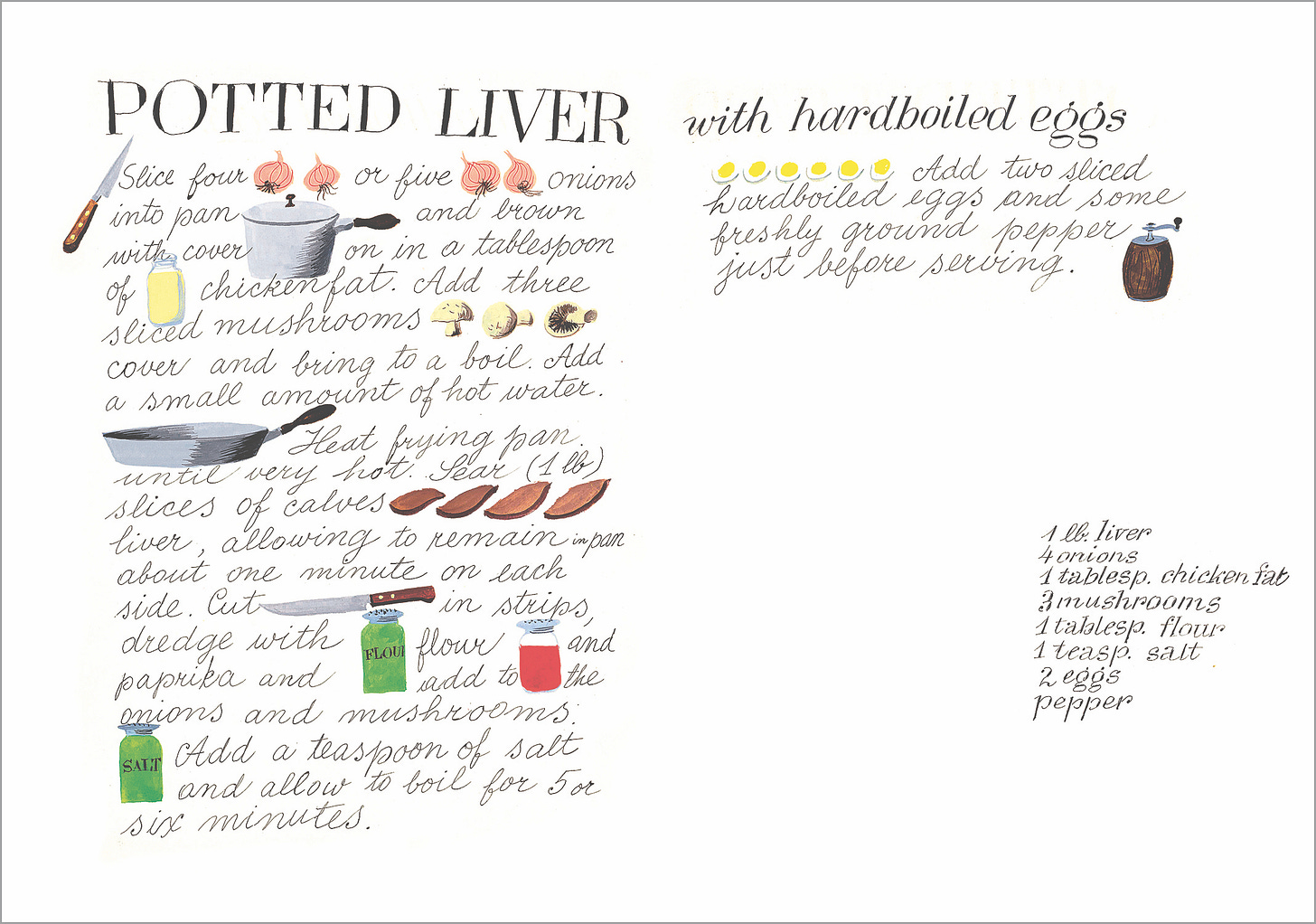

Potted Liver

In another stroke of creative genius, Pineles transformed the method into the art itself in her recipe for potted liver with hard-boiled eggs. The instructions fill the left page, interspersed with tiny illustrations that feel almost hieroglyphic. She composed the page expertly to allow the method to break at a logical point, separating the preparation of the liver from that of the eggs.

Again, the large empty field on the right calls attention to itself—maybe this is where the prepared dish was to be placed? We will never know, but Pineles’s lively spirit remains among us in these pages, piquing our curiosity, delighting our eyes, and inviting us to steal a little time away on our own to cook something delicious.

Many thanks to Carol Burtin Fripp and Robert Fripp for sharing their memories of Pineles, and to Sarah Rich, Wendy MacNaughton, and Roberto de Vicq for their insights into her work and their efforts to bring Pineles’s sketchbook into publication. For a deeper dive into Pineles’s life and work, please see Cipe Pineles: A Life of Design by Martha Scotford.

Frances Baca is principal of Frances Baca Design and Consulting in Berkeley, California. Her studio focuses on editorial design and creative direction and consulting. She has designed and art directed countless cookbooks, and she was the founding design director of the much-loved food and culture journal Gastronomica. Her work has been recognized by the James Beard Foundation, the Society of Publication Designers, the Association of American University Presses, Graphic Design USA, the New England Book Show, and Bookbuilders West. You can hear more about her thoughts on cookbook design in the Salt + Spine podcast.

This is amazing, the book and the essay!

I loved this article. I bought this book in Healdsburg CA. I mainly bought it because of her artwork. I fell in love with it, and the simple family recipes was very appealing to me also.