Inside the World of Art Cookbooks

Cookbooks as art! Cookbooks by artists! Cookbooks inspired by art!

Howdy cookbook fans!

Today is a TREAT: we’ve got art historian/curator/critic Andrea Gyorody here to walk us through the world of art cookbooks—that is, cookbooks by artists, cookbooks inspired by art or artists, or cookbooks that are themselves art. She just launched a newsletter about food and art called Weekly Special, check it out. Now, let’s get arty:

An Art Historian’s Guide to Art Cookbooks

The rise of what I call the “art cookbook”—recipe books written by or about artists, or with art as a central motif—derives from the ever-increasing appearance of food in art. Still life painting has long used food as a tantalizing prop, but 20th-century artists took food in a radical new direction, conceiving of food and the act of eating as the literal materials of their art-making. Beginning in the early 1960s, pioneering Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri hosted dinners and glued the remnants, dirty dishes and all, to sturdy boards exhibited like paintings. Around the same time, Dieter Roth sculpted self-portraits from chocolate; Alison Knowles made salad as public performance art; and Carolee Schneemann produced a film titled Meat Joy, recording a sea of bodies orgiastically rolling around with raw meat, fish, and poultry.

What Spoerri called “Eat Art” has only ramped up since then. In just the last decade, I’ve eaten crispy pork and a koji hot dog; enjoyed a stout and a sparkling apple juice; tossed back a strong espresso; slowly savored a mint candy and, elsewhere, a cup of butterfly tea; and nibbled on a seaweed bar that stained my tongue black—all of which were foodstuffs created by artists, framed as artworks, and exhibited at galleries and museums.

Art cookbooks are yet one more way that art and food have intermingled. And while the subgenre might sound painfully niche, such books encompass everything from Mary Ann Caws’ Modern Art Cookbook, which puts work by modern artists and writers in dialogue with recipes from their everyday lives, to Consider the Tongue, an artists’ book by S*an D. Henry-Smith and Imani Elizabeth Jackson that explores slavery’s legacies through recipes, poems, and photographs.

As I began assembling a list of art cookbooks to share with readers of SPN, I found myself arranging them into the loose taxonomy that follows, with some favorites spotlighted in each category. This compendium is by no means comprehensive, but it’ll give you a small taste of what art cookbooks have to offer.

The Monographic Cookbook

Artists are often fascinating figures, eccentrics with lives full of passion, intrigue, and scandal (or so Hollywood would have us believe). It’s not a stretch to wonder what they ate, whether alone in the studio, entertaining at home, or out on the town with other fabulous people.

For Impressionist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, work and sociability were inextricable. As The Art of Cuisine attests: “Visitors were astonished to see that the artist’s studio, in addition to being a workplace, was also a bar so well-stocked that he could offer them an infinite variety of cocktails—essential, according to him, for the proper contemplation of a painting.” That Belle Époque joie de vivre also courses through cookbooks from the tables of Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Auguste Renoir, and Claude Monet, whose enduring fame has inspired no fewer than three cookbooks. One of them, based on the artist’s cooking journals, boasts recipes adapted by famed French chef Joël Robuchon, who notes with awe how difficult these preparations would have been in a Giverny kitchen with zero modern amenities—not even an icebox!

On the other side of the Atlantic, we have cookbooks from the kitchens of painters Jackson Pollock, who made a mean apple pie, and Frida Kahlo, who was expected to perform the roles of artist and committed housewife, keeping Diego Rivera and all of their illustrious friends well-fed with traditional Mexican fare. Georgia O’Keefe’s austere sensibilities are documented in two cookbooks, and while I doubt anyone needs a recipe for steamed carrots or cottage cheese and orange salad, anecdotes about O’Keefe’s disciplined life are surprisingly tender and worth a read.

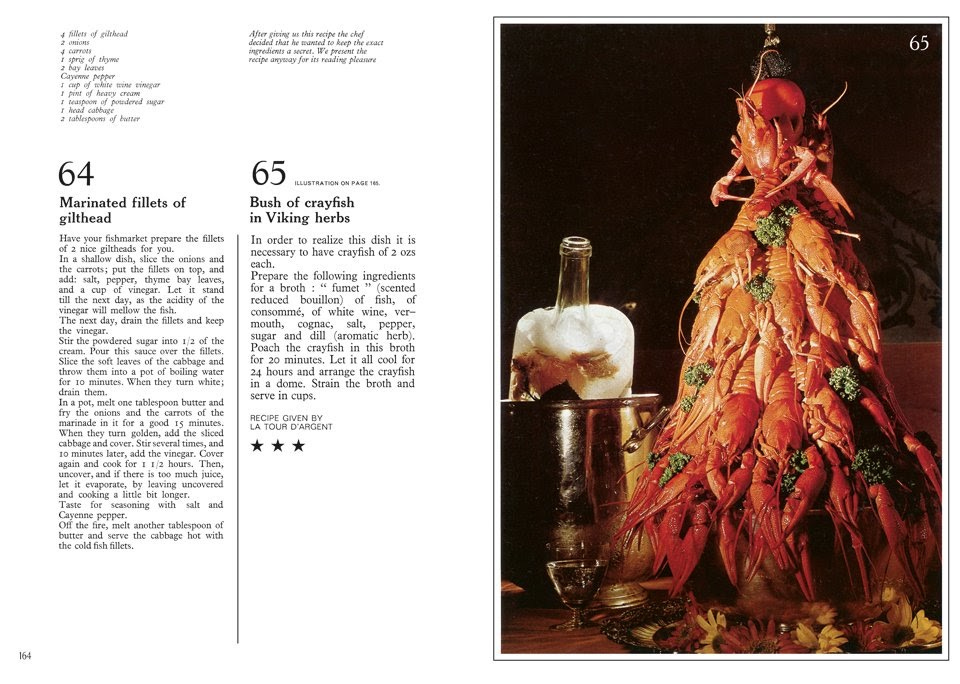

If you’re going to add any monographic cookbook to your collection, however, look no further than Salvador Dalí’s recently reprinted Les Dîners de Gala. The book’s full-color photographs are awash with a ’70s glow, appropriate for outlandish Surrealist feasts featuring icebergs of prawn parfait, savory pies decorated with leeks cut to resemble palm trees, and whole stuffed peacocks perched on platters of braised quails.

Not exclusively focused on the meals of a single artist, Mina Stone’s Cooking for Artists shifts the “from the kitchen of…” model in a refreshing direction. The book is filled with simple Greek- and Persian-inspired recipes she cooked for the staff at artist Urs Fischer’s studio and for events at Gavin Brown’s gallery, illustrated with photos from Stone’s blog and quirky drawings by artist friends. It’s less about what artists like to eat and more about what Stone likes to feed people, with the art world as her backdrop. I’m eagerly awaiting her follow-up, set to be released this September.

The Compilation Cookbook

The scrappier cousins of the monographic books, compilation cookbooks are equally revealing in what they capture about artists’ lives at a particular moment in time and place. The paradigmatic example is The Museum of Modern Art Artists’ Cookbook, a spiral-bound collection of recipes and conversations with 30 notable painters and sculptors, published in 1977. The recipes range from Helen Frankenthaler’s elegant Poached Stuffed Striped Bass to Andy Warhol’s droll instructions for heating a can of Campbell’s tomato soup. It’s the perfect snapshot of old-guard seriousness and young-gun absurdity coexisting side-by-side, exactly as it did in the art world.

Many more such compilations have followed, including The Photographers’ Cookbook, assembled by the George Eastman Museum in the late 1970s; The Artists’ and Writers’ Cookbook (inspired by a 1961 book of the same title); the endlessly amusing Synergetic Stew: Explorations in Dymaxion Dining, put together for Buckminster Fuller’s 86th birthday; and The Videoart at Midnight Artists’ Cookbook, released just last month.

The Starving Artist’s Cookbook, from 1991, is the most elaborate of the bunch. Produced by the artist-duo Paul Lamarre and Melissa Wolf, who go by the acronym EIDIA, the project encompasses a ring-bound book of typewritten recipes (most of them delightfully bizarre) and a series of videos with a total runtime of nine hours, documenting artists at work (and onstage) in their kitchens.

Julia Sherman’s Salad for President, based on her blog of the same name, is imbued with a similar reverence for what artists have to teach us about cooking, eating, and living. A deftly curated take on the compilation cookbook, Salad for President layers Sherman’s own salad recipes with interviews she’s conducted with artists and folks she calls, cheekily, “salad artists”—notably Alice Waters and Ron Finley. Everyone contributes a recipe, amounting to a volume with salads for every palate and season.

The Cookbook that Takes Art(ists) As Inspiration

Monographic and compilation cookbooks both tend to fetishize artists’ lives—their friendships, romances, lavish parties, weird diets, favorite hangouts. Cookbooks that take art(ists) as inspiration instead explore how to turn artworks, or the essence of the artists who made them, into edible foodstuffs. Though art history is full of possible material, this is a surprisingly slim category with two standouts.

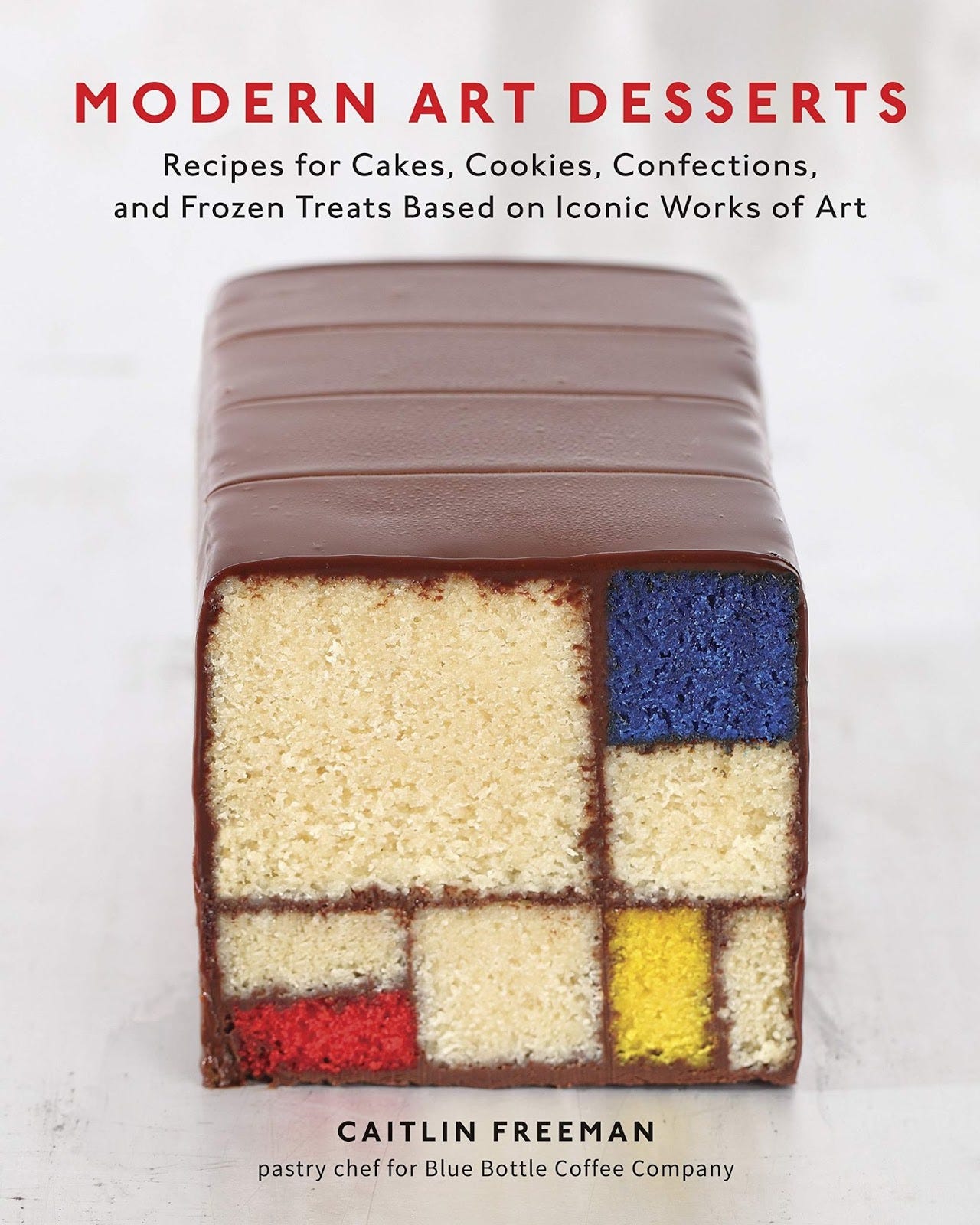

Pastry chef Caitlin Freeman’s Modern Art Desserts catalogues the treats she and her team created for the Blue Bottle-operated SFMOMA café, using works in the museum’s collection as prompts. In addition to offering extremely precise instructions for producing, among other delights, the Piet Mondrian cake that appears on the cover (above), the book also gives insight into Freeman’s process, sharing some of her drawings and collages, and even the details of failed attempts and snafus—the most amusing of which involved a cease-and-desist from Richard Serra, who demanded the café stop producing a cookie plate based on his 1969 sculpture of precariously balanced lead plates. (Saddened, Freeman obliged, and created a new assemble-it-yourself cookie sculpture, which appears in the book, based on Barnett Newman’s work instead.)

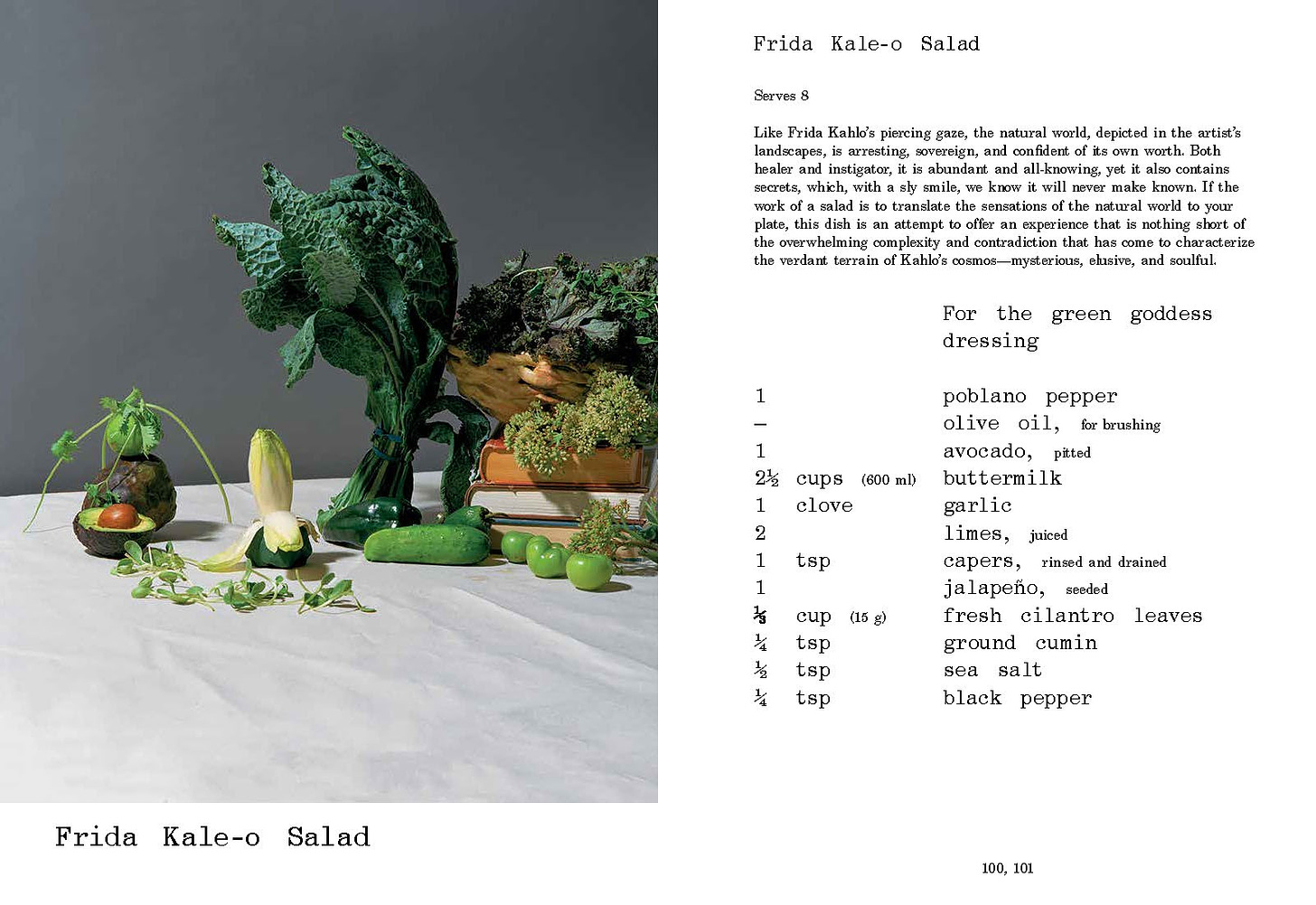

Esther Choi’s Le Corbuffet: Edible Art and Design Classics takes a less literal approach. Based on a series of “participatory events that used food as a medium to explore how cultural canons are consumed and reproduced,” the book features Choi’s photographs of dishes punnily named after modern artists and architects: Robert Rauschenburger, Quiche Haring, Frida Kale-o. Sincere in its aesthetic and political provocations, Choi’s work also effectively parodies the self-seriousness of molecular gastronomy and farm-to-table cooking.

The Cookbook as Artwork

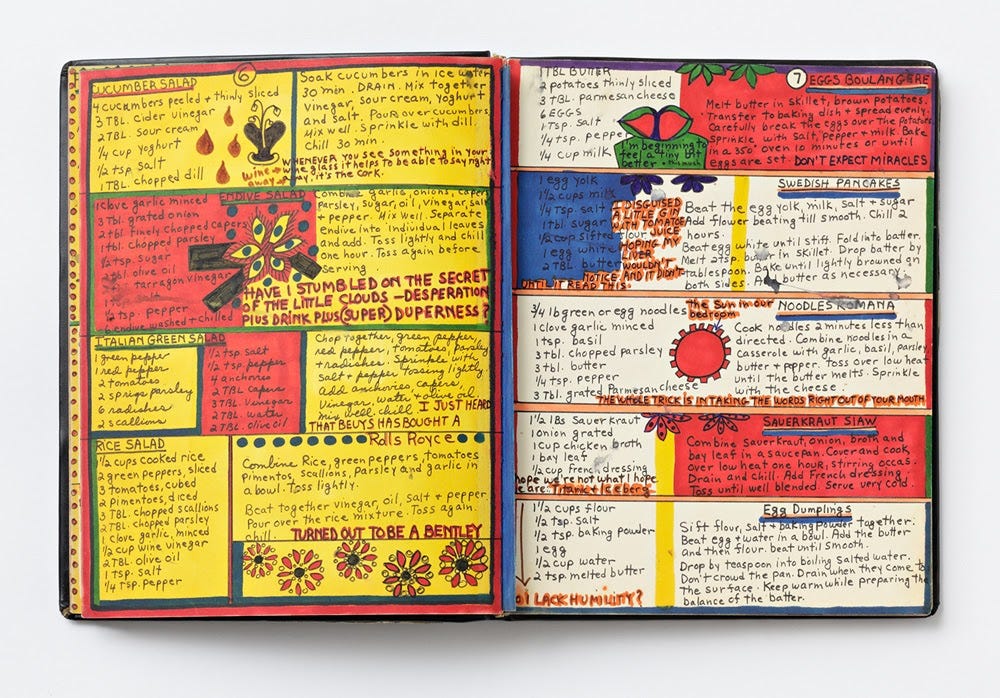

In Dorothy Iannone’s brief foreword to A Cookbook, originally published in 1969 and reprinted in 2019, she looks back on her life in the late 1960s, when she was working simultaneously on a series of erotic paintings and on a recipe book. “While I painted,” she writes, “I played my favorite LP records. Cigarettes and vodka, music and song, accompanied my journey through the nights in my atelier. And now, reading the comments with which each page of the Cookbook is adorned, I realize that nothing less than love could have prompted the transforming of an accumulation of recipes into a work of art.”

Iannone’s vibrantly rendered “accumulation of recipes” represents one of the best examples of the cookbook-as-artwork, a category that boasts volumes ranging from F.T. Marinetti’s 1932 Futurist Cookbook, replete with manifestos and dinner “formulas,” to Andy Warhol’s exceptionally charming (and very rare) illustrated cookbook Wild Raspberries, to Ryan Gander’s Artists' Cocktails, a compendium of cocktail recipes submitted by fellow artists in connection with a 2012 project called the Maybe Center for Conviviality, sponsored by Absolut.

A slew of recent books have been especially compelling, including Antto Melasniemi and Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Bastard Cookbook, which merges Thai and Finnish culinary traditions; S*an D. Henry-Smith and Imani Elizabeth Jackson’s moving artists’ book Consider the Tongue; and Demetria Glace’s just-published Leaked Recipes: The Cookbook, an irreverent collection of recipes culled from troves of hacked emails.

The book I love most, though, is Michael Rakowitz’s A House with a Date Palm Will Never Starve, a beautiful cookbook dedicated to a single ingredient: date syrup. In 2018, Rakowitz reconstructed the Lamassu, a major work of antiquity destroyed by ISIS, in London’s Trafalgar Square. Created from more than 10,000 flattened cans of date syrup, the monumental sculpture pointed to the imperiled state of culture—artistic, culinary, and otherwise—in Rakowitz’s ancestral homeland, Iraq. A House with a Date Palm grew out of the Lamassu project, bringing together date syrup recipes from the artist’s mother, his friends, and a handful of chefs. The book is, as the artist puts it, “a way to taste the sculpture.” No sculpture has ever tasted so bittersweet.

Andrea Gyorody is an art historian, independent curator, and critic. She is Founding Editor of Digest, a publication dedicated to exploring global foodways, produced by the LA-based non-profit Active Cultures. She has also just launched a newsletter called Weekly Special, which looks at one food-based artwork a week. You can find more of her arts writing at Hyperallergic, ARTnews, and Artforum, and learn more about her past and current curatorial projects on her website.

In case you missed Tuesday’s issue: Sammy Hagar’s writing a cocktail book! Everyone spent quarantine writing recipes! Seriously, everyone! Plus Alison Roman’s old apartment, a book from the first Thai restaurant in the US, and an 83-year-old first-time cookbook author with an amazing Abilene accent! And much more! Become a paid subscriber and check it out: