Not Just How, But Why: Recipes That Teach

Instruction versus education, via recipe.

Howdy cookbook fans!

And welcome to a rare MONDAY edition of Stained Page News. This issue was supposed to come out Friday, but due to a professional emergency, it got bumped to today. (CTRL-S constantly, friends. CTRL-S! Do it now! DO IT NOW.)

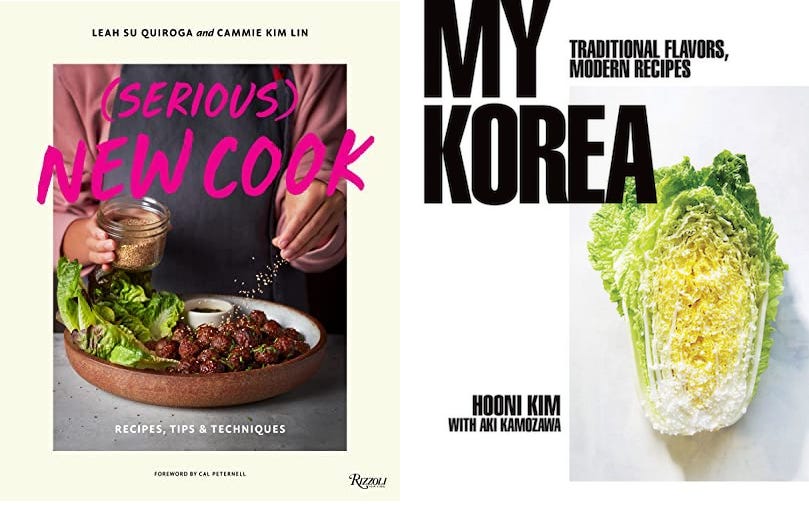

Anyway! Today a treat for you: NYU writing professor Cammie Kim Lin is here to discuss the difference between recipes that instruct and recipes that teach. Her new book, (Serious) New Cook, which she wrote with her sister Leah Su Quiroga, focuses on the latter. Recipes that instruct are fine for experienced cooks, but beginner, intermediate, and advanced home cooks can all benefit from recipes that teach. Lin should know: in addition to writing, she has studied educational pedagogy and food studies. A triumvirate of specialties that make her the perfect person to dive into this topic!

Cammie, take it away!

Today's issue of Stained Page News is brought to you by Hardie Grant Publishing and Giuseppe’s Italian Bakes, the first cookbook from Giuseppe Dell'Anno, winner of 2021's Great British Bake Off. During his time in the tent, Giuseppe won hearts the world over. Now this Star Baker shares his skill, knowledge and love of baking through over 60 new sweet and savory recipes.

Not Just How, But Why: Recipes That Teach

—by Cammie Kim Lin

During a recent talk at the university where I teach, I was interviewed about my new cookbook by a colleague I know to be an excellent cook. I asked her, “When you read a recipe that says, Dust the cake with powdered sugar, do you know what that means? Or, grease the cake pan and line it with parchment? (“Of course.”) Then I turned to the audience, mostly undergraduate students. “And you? Would you know how to do that, or why?” A few nodded, but most laughed and shook their heads. No way.

All recipes instruct, but not all teach. While the two words share a lot of meaning, there is a fundamental difference between them. To instruct is to provide commands, to tell someone what to do. To teach is to guide someone to understand not just what to do, but how and why to do it. When you learn that, you become more fluent, more adaptable, more creative. When you understand how and why to do something, you can apply it to future situations, not just the same situation in the future. In other words, you learn not just to make a dish, but to cook, more generally.

Cookbook author and cooking instructor Molly Stevens writes recipes that teach—a lot. It comes as no surprise that Stevens has been named Teacher of the Year by both the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP) and Bon Appétit. She describes herself as a “teacher who writes,” and indeed, she writes recipes that teach. Just listen to this step from her Simplest Tossed Green Salad recipe (in All About Dinner: Simple Meals, Expert Advice), which follows a full-paragraph step explaining how to prepare greens for a salad:

2. ADD THE GREENS. Make sure the leaves are completely dry; any moisture on the greens will water down the salad and make it droop. Pile the greens in the bowl a handful at a time, inspecting them as you go. Nothing ruins a simple salad more than a slimy leaf. If there are any very large leaves, you may want to tear them into smaller pieces so they are more manageable. A mix of shapes and sizes is nice, especially if you like to eat your salad with a knife and fork, as I do. If you’re a fork-only person, gently tear any large leaves into bite-size pieces without scrunching or bruising them. You could use a knife, but I find it less convenient than a simple tear.

We’ve only gotten as far as putting greens into a bowl (a step most recipes would not even acknowledge), and look how much Stevens has taught us already.

On the other end of the spectrum lie the exceptionally succinct recipes of food writer and cookbook author Ali Slagle. In a recent episode of the podcast Everything Cookbooks, hosted by Stevens and Andrea Nguyen, author of Vietnamese Food Any Day and The Pho Cookbook, Slagle talked about her bare-bones recipe writing approach, saying she writes for people who already “have a good idea and understanding of cooking and just need new ideas.” Her clear, concise instructions get the job done—to delicious effect—for those who already know their way around the kitchen. Here she does it in the first two (of only three total!) steps of her Bok Choy-Gochujang Omelet recipe:

In a measuring cup, whisk together 5 eggs and the zest of 1 lime. Season with S&P.

In a medium bowl, stir together 1 teaspoon sugar, 2 teaspoons gochujang, 1 teaspoon toasted sesame seeds, ½ teaspoon toasted sesame oil, and the juice from half the lime (about a tablespoon). Thinly slice 8 ounces baby bok choy (about 2 large) crosswise. Stir into the gochujang mixture and season with S&P.

For reasonably seasoned cooks, these instructions are perfect. They don’t need to be taught what zest is or how to get it, what gochujang is and what substitutions might work if you can’t find it, how to toast your sesame seeds, or what it looks like to slice baby bok choy crosswise. To most already-cooks, these things are obvious, so a succinct recipe is just what they want to get this omelet on the table fast.

The titles of Slagle’s and Stevens’s books are telling: Slagle’s I Dream of Dinner (So You Don’t Have To) lives up to the name. She dreams up inspiring recipes for good cooks who need some new ideas. Stevens’s All About Dinner, on the other hand, delivers on its name, too, giving readers all they need to become masters not only of the dishes at hand, but of dinner, in toto.

Between these two extremes lie most others. Word count and design restrictions undoubtedly dictate the way many recipes are written. (Getting that sorted out before an author starts writing can save a lot of words from the cutting room floor!) But beyond that, it really comes down to a combination of writing style, audience, and pedagogy (if there is one).

J. Kenji López-Alt, author of The Food Lab: Better Home Cooking Through Science and The Wok: Recipes and Techniques, does a tremendous amount of teaching in his cookbooks, though his recipes still tend to stick to instructions. In other words, he first teaches, showing and explaining the how and why of everything, and then he instructs. This is perhaps the most common approach of cookbooks that teach. The cooking lessons, explanations, and takeaways—whether in the front matter, special technique sections, extensive sidebars, or highly informative headnotes—tends to contain most of the teaching. Then, the recipes themselves stick fairly close to instructions only.

Samin Nosrat takes a somewhat similar approach (albeit to a very different effect) in her bestselling Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat. She dedicates the first 200 or so pages to the teaching and the second 200 to the recipes. Smart tips and extra details appear here and there within the recipes, but by and large, they stick to instructions, detailed as they are.

This teach-then-instruct approach seems commonsensical. Readers who are interested and have the time can undertake the lessons found in the notes or front matter (or occasional in-between sections), while those only needing straightforward instructions—like my colleague, the fine cook—just skip right to it. But what of the readers with much to learn but who don’t quite have the time or the drive to read through all that rich front matter?

Where individual recipes fall on the instruct-or-teach spectrum usually reflects the specific audience a cookbook author is writing for. How committed to learning are they? How fascinated by all the geeky details might they be? And how much can be assumed about readers’ prior experience with techniques and ingredients being used?

When I wrote (Serious) New Cook with my sister, Leah Su Quiroga, a former head chef at Chez Panisse, we wanted to reach an audience few others have attended to: young adults who know good food, but don’t yet know their way around the kitchen. To do that, we set aside all assumptions about their prior culinary knowledge, yet we accepted, based on experience with the age group, most of them wouldn’t go in for extensive front matter or instructional lessons. Ultimately, that meant working a lot of teaching right into the recipes themselves.

Hooni Kim, New York-based chef and author of My Korea: Traditional Flavors, Modern Recipes, has a different reason for writing recipes that teach. He says his motivation is to help readers better understand him and his views, “which aren’t always popular today.” He explained that, even as many of his Korean and Korean American contemporaries move away from traditional Korean techniques and dishes, he finds himself moving more and more toward them. In fact, he’s even been criticized for it, having been “called racist for not being a fan of MSG,” an ingredient that, while often seen as traditional, only goes back to its invention in the early 1900s—rather young in the scope of traditional Asian cuisines. So when Kim writes a recipe calling for traditional techniques, he often expands upon the instructions with explanations and variations. He’s explaining why he cooks the way he does, and teaching us how to do the same.

And then there are wonderfully non-traditional cookbooks like Tamar Adler’s An Everlasting Meal and Cal Peternell’s Twelve Recipes, which read beautifully from cover to cover, the recipes almost impossible to disentangle from the stories and lessons. Perhaps more at home on your bedside table than the kitchen counter, they don’t make handy reference books, but if you can hold onto even a fraction of their wisdom and storytelling, you don’t need to refer to the instructions in their recipes. Peternell really understands this; he titled his second cookbook A Recipe for Cooking. Taken as a whole, the book is indeed a recipe that teaches (to cook). Adler, it’s worth noting, is working on an “easy to flip through” version of her book, called The Everlasting Meal Cookbook: Recipes for Leftovers A-Z, set to publish in March, 2023.

No cookbook and no recipe will serve all readers the same. Nor should it. Often we just need some inspiration or want to get a tasty dinner on the table. But for those who look to cookbooks to deepen not only their repertoires but also their cooking knowledge, skills, and understanding, it’s worth taking the time to sit with a cooking book or to work your way through a cookbook full of recipes that teach.

Cammie Kim Lin is the co-author (along with Leah Su Quiroga) of (Serious) New Cook: Recipes, Tips, & Techniques, a cookbook for young adults or newish cooks of any age who are ready to level up in the kitchen. She is a writing professor at New York University, and her scholarship includes educational pedagogy and food studies.

Really great examples of books here! And great insight into what works -- and why!

absolutely love this