Sticklers, Improvisors, and “Following” Recipes

Oh you know just what I think about when I take time off.

Howdy cookbook fans!

And welcome back to Stained Page News! Unless you’re a paid subscriber, this is the first you’re hearing from me this year, and I am so glad to be back. Today I wrote a little essay about some ideas I’ve been chewing on when I write recipes: how do readers interpret recipes? How should a recipe be written when you know some readers will go off script? How can recipes encourage improvisation, and should they? Or is that too confusing? What do I expect readers to actually do with any given recipe I write? How should a recipe writer best set up a wide range of readers for success?

Nerd stuff! Let’s go!

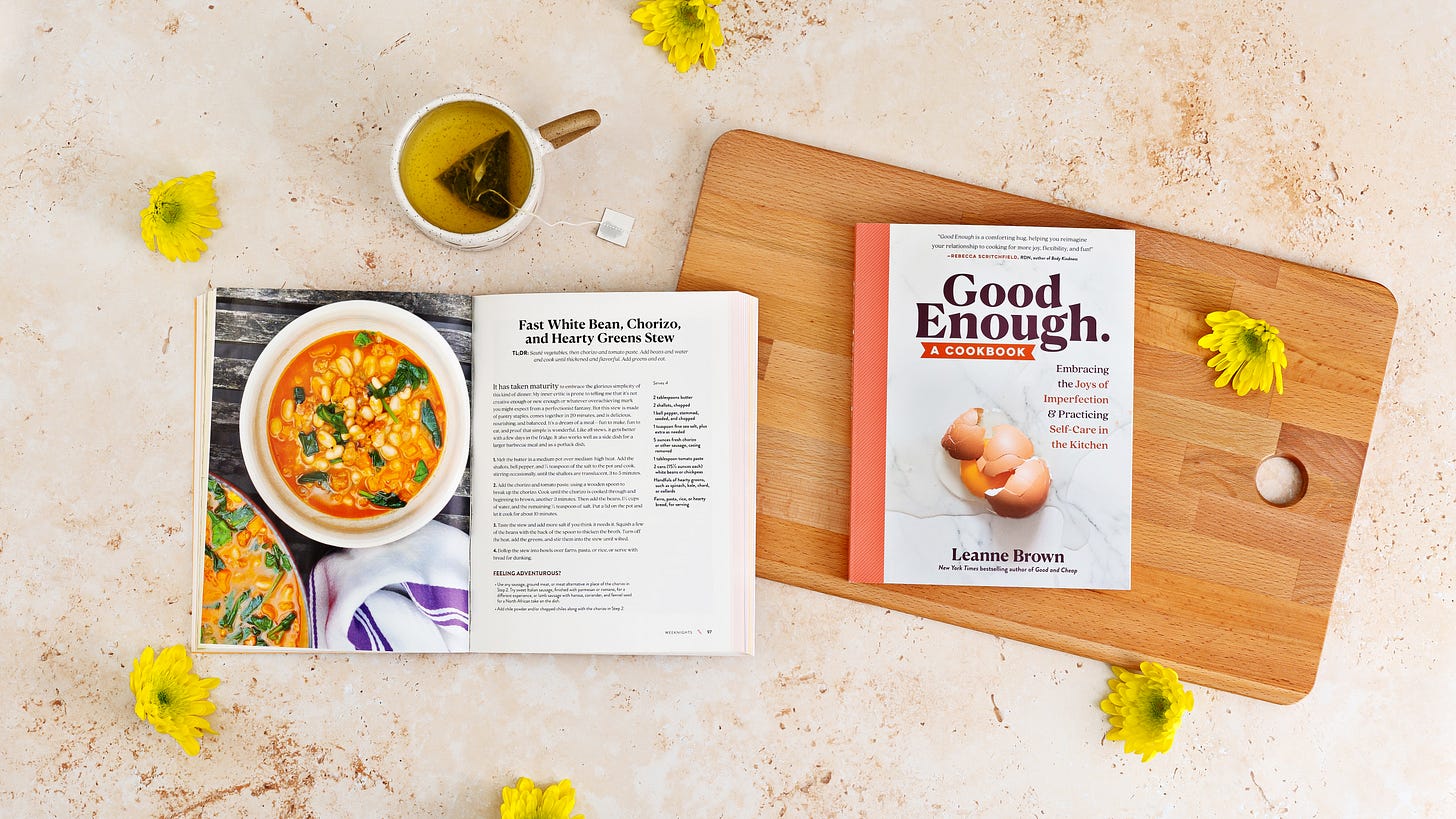

Today’s issue of Stained Page News is brought to you by Good Enough: A Cookbook by Leanne Brown, author of the New York Times bestselling book Good and Cheap. A groundbreaking cookbook, Good Enough approaches food and cooking through the lens of self-care, mental health, and forgiveness. Filled with essays that delve into the feelings that can surround food—anxiety, self-doubt, guilt—Brown’s overarching message is that if “you cook with self-compassion you can enjoy the experience, appreciate the great meals, laugh at the not-so-great ones, and generally live your cooking life with way less fear.”

Alongside these heartfelt essays are 100 flexible, soul-satisfying recipes, from a Citrus Refresher Pasta to Here and Now Jalapeño Honey Biscuits to an easy Cozy Cold-Weather Bolognese and Lemon Poppyseed Drizzle Cakes. Use promo code STAINEDPAGE for 20% off of Good Enough by Leanne Brown when you purchase on workman.com.

Sticklers, Improvisors, and “Following” Recipes

Every once in awhile, a tweet will go viral boasting that if a recipe calls for 2 cloves of garlic, the tweeter will use 5. Or 8. Or 20. The declaration is made with a smirk: the tweeter is pulling something over on the recipe writer. They know better. The frequency with which this particular tweet goes viral shows how common this sentiment is, and in my experience, recipe writers know that unless the quantity is outsized— say an entire head of garlic—readers are probably going to use as much garlic as they please. That’s how it goes…but the writer still needs to call for a number of cloves in the ingredients list.

I’ve been doing a lot of recipe writing lately. And unlike recipe development (the actual construction and testing of the dish in a kitchen), recipe writing has a lot more to do with language: how the writer instructs the reader, and, crucially, what the writer expects the reader to do with that instruction. Some elements of a recipe are critical to the outcome of a dish, but others have a little more wiggle room. And it’s up to the writer to make clear to the reader which instructions fall into which category.

Take caramelizing onions. In 2012, a Tom Scocca essay in Slate took recipe writers to task for “lying” about how long it takes to caramelize onions. Scocca found a bunch of examples where recipe writers claimed onions would brown in 5 or 10 minutes, when in fact, the caramelization process takes closer to 45 minutes. It is a process that cannot be rushed or cheated, and, if caramelized onions are critical to the dish, the cook time should be emphasized accordingly in a recipe.

On the other end of the spectrum are recipe instructions that are open to interpretation. In my own book, The Austin Cookbook, there’s a recipe for grilled lacinato kale served with a sprinkling of lemon zest, pine nuts, Parmesan, and olive oil. It’s a pretty simple recipe, and the instructions call for “1 bunch kale.” More than any other recipe in the book, people ask me about this one. How much kale? What size bunch? The answer, which I know people don’t like, is that it doesn’t much matter. Big bunch, small bunch: as long as you taste for seasoning at the end, it’s going to be fine.

Confusing the matter, readers don’t all follow recipes in exactly the same way. Consider two categories: sticklers and improvisors. People seem to fall into these categories regardless of their skill level; I know recipe sticklers who have cooked in Michelin-starred kitchens, and absolute novice improvisors who seem surprised there are people in the world who actually read recipes all the way through. I fall somewhere in the middle: while I will absolutely go off-script to save a dish that’s clearly not working, I often stick to recipes far past what common sense would tell me to do. (What can I say, I am forever in search of a new trick that will forever change how I think about a specific dish, technique, or ingredient. Often to my detriment.)

So what is a recipe writer to do? Write for the sticklers, who find comfort in detail? Assume the reader will add as much garlic as they damn well please, regardless of what you write? Strike a balance between the two? In my own writing, while I believe encouraging improvisation makes people better and more confident cooks—it doesn’t matter how much kale you use, and honestly you could probably make this with cabbage or collards or other sturdy greens—I know that confuses and frustrates some readers.

The answer, I find, is simply writing longer recipes. Using more words. Being generous, yes, but also writing persuasively: if something is important, I will say so, and I will tell you why. Yes, caramelizing onions really takes that long. No, you can not use pre-shredded cheese in pimento cheese because it is coated with anti-caking agents, you must grate it yourself. I’m sorry, I know the pre-shredded is easier. Trust me. Trust me.

That trust needs to go both ways, though. The internet is a graveyard of recipes littered with comments about how “I hated this recipe. I subbed tofu for tempeh and left out the soy and used balsamic vinegar instead of lime juice and ate it cold instead of hot.” And while it would be easy to assume a better outcome had the commenter followed the recipe to the letter, the truth is following any recipe “to the letter” is next to impossible. Different kitchens, different equipment, different ingredients, different skill levels, different cooks, different interpretation of instructions: all of these variables conspire to make following a recipe exactly as the author intended it nearly impossible. Even for sticklers!

In other words, the concept of “following a recipe” is much more complicated than it seems. While recipe writers may take some best practices from coding principles, cooks are not computers following a program. Every time someone cooks a recipe, the outcome will be different—even if the difference is slight. This is of course why recipes need to be tested, both by the writer and, ideally, by other home cooks in a variety of kitchens. But for every stickler out there, there are just as many improvisers. For every slight change in a batch of blondies due to altitude or brand availability, there’s someone out there using shredded coconut instead of chocolate chips and deciding that, actually, browned butter might be nice.

It’s a balance, then, between writing for sticklers and improvisors. Tell readers which steps are important and why. Tell them where they can make substitutions if they like. Give enough detail for comfort, don’t suggest so many variations as to overwhelm. Use more words, but try to keep your language simple. Ask readers to trust the recipe; trust them as home cooks in return.

That’s all for today! I hope you liked this essay. It was nice to write about cookbooks and recipes again, I’ve missed it. Have a good weekend and see you again soon.

I enjoyed the essay! I’m pretty much a stickler. I subscribe to NYT Cooking and always read the comments, many of which are like you describe….”I subbed this for this and this for that” until practically nothing is the same. I also get frustrated by all the people who want to cut back the sugar, and as some of the follow up commenters say, “ Make a different recipe!”

I love this, Paula. After a few years now of writing recipes with my own evolving style guide, I do think you need to strike that balance, and to give them _advice_ as much as instruction, and somehow distinguish between the two. And also not scare them away or bore them. Doing that well is HARD!