3 Books That Changed My Life

Or why I am the way I am about cookbooks.

Howdy cookbook fans!

A little bit of a trip down memory lane here, considering a few books that shaped how I think about cookbooks. I hope you enjoy it! Paid subscribers, tomorrow sees the return of book club with a slightly different format—for the month of June, we’ll be considering NOODLES in all their forms, and books featuring them and written about them. If you’d like to join the fun, hit that big orange button and become a paid subscriber:

This issue is brought to you by Goldilocks! There’s no room for gizmos or gadgets in my kitchen (too many cookbooks), so I only go for high quality, essential, affordable cookware. Goldilocks is on it: You can’t go wrong with any of their pro-level kitchen gear, but a great place to start is this bestselling stainless steel cookware set. Check it out:

This week, the AC in our house broke. Or, more accurately, flooded: two days in a row, just after dinner, sheets of water came gushing out of the metal box onto the floor, a place where water has no business being.

The second time the HVAC repairman came, he managed to fix it. And when I came back into the living room with my wallet to pay him, I found him staring at my bookshelves.

“Y’all must get takeout a lot,” he said, laughing.

Sometimes I forget that how I am about cookbooks is not normal. I’m not quite sure how I got this way, either. I just remember one day when I was 16 and hanging out at Borders (as one did as a 16 year old with shit else to do in The Year 2000) it suddenly occurred to me that I could get a cookbook. That was how it felt: not that I chose to buy a cookbook, but as though a permission had been granted to me. Like getting my driver’s license had felt a months before, or like ordering a beer at a restaurant would a few years later. A door had opened. To this day, it has not closed.

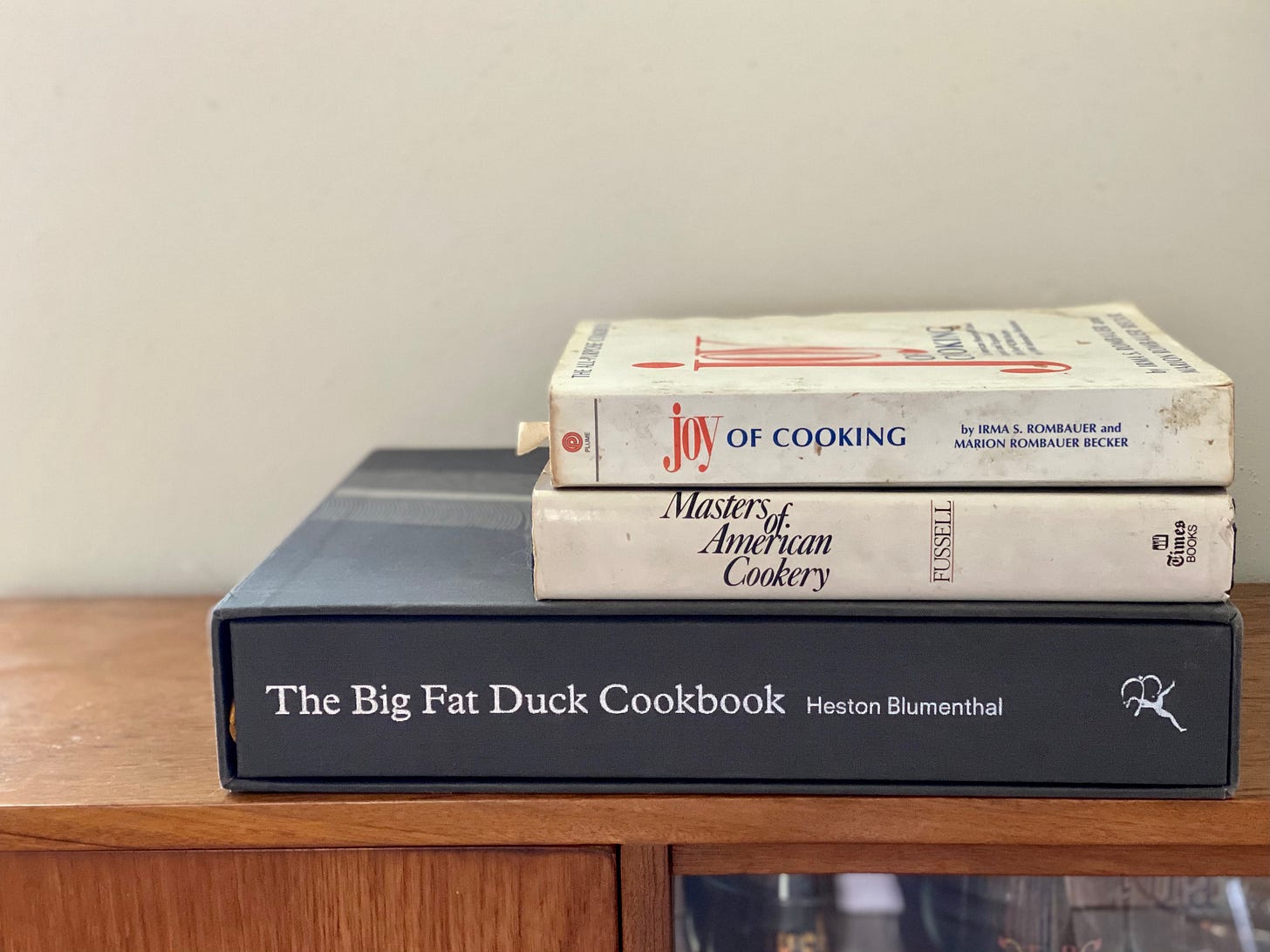

It was the 1997 edition of The Joy of Cooking. The Maria Guarnaschelli-edited, much debated edition. Kim Severson called it “the New Coke of cookbooks” in The New York Times; she also called it “a contemporary, efficient and thorough study on cooking with impeccably researched recipes.” Readers at the time didn’t like its clinical, instructional, third-person voice, and missed what Guarnaschelli cut from the 1970s edition. I love it. It will, forever, have a spot on my shelf.

In college, that shelf got bigger, and included my grandmother’s copy of Mastering the Art of French Cooking. It’s a cliché to say Julia Child’s first cookbook made an impact on the life of a food writer, but in my case it wasn’t the book itself, it was something someone wrote about it. The September 2005 issue of Vogue contained a brief, glittering essay by Betty Fussell1 that was ostensibly about Claire McCardell dresses and what they meant to her as a young, post-war housewife. But it was also about dinner parties as theater, and the power that one might find in taking control of the kitchen. To me, an intoxicating concept.

After that, I sought out every book by Fussell I could find, and in them found someone who thinks deeply not just about food, but how it’s written about as well. Her Masters of American Cookery looks at the lives of MFK Fisher, James Beard, Craig Claiborne, and Julia Child, and the ways their lives intersected and didn’t, and the way their writing changed how Americans cook and eat. Here was someone who took these authors as seriously as my professors took Whitman and Milton and Ginsberg! Another door opened, one that, I thought, might lead to a professional calling.

Unfortunately, I assumed the venue for that calling was academia. And as I applied to (and was rejected from) graduate programs that kept telling me they didn’t have anyone who could help me—one faculty member at a university I only kind of wanted to attend told me studying cookbooks as literature was “too damn exotic”—I started writing. First for my own blogs, and later for a website that looked at culture through the lens of food, Eat Me Daily (RIP).

At the time, I was working as the office manager for a catering company, a job I hated. And then, through some accounting error, caught a windfall in the form of a larger-than-anticipated tax refund. Instead of doing what I should have done with it—fixed the cracked windshield on my 2001 Honda Civic—I decided to buy a cookbook so I could pitch a review of it. Specifically, The Big Fat Duck Cookbook by Heston Blumenthal.

The book is a bit of a spectacle. When it came out, Raymond Sokolov wrote in the Wall Street Journal:

The Big Fat Duck Cookbook is the biggest (10 pounds with box), the most expensive ($250) and the most flamboyant (four brightly colored silk marker ribbons, uncountable full-page color illustrations and gatefolds, mainly caricatures of Mr. Blumenthal gliding through a dreamland of foods) cookbook in a bumper year. But like its author, who turns out to be a clear and even affecting writer, there is gravity holding the rocket in orbit.

The “bumper year” Sokolov describes there is 2008, a year that saw releases from a bunch of fancy white male chefs with a galaxy of Michelin stars including Joël Robuchon, Grant Achatz, Eric Ripert, Ferran Adría, and others. Quite a publishing trend for the year that saw the economy crumble to absolute pieces.

It was also the year I wrote my first cookbook review for Eat Me Daily, of Blumenthal’s massive tome. And in the review, that $250 price tag was a major sticking point. ($250 list price—I somehow snagged my copy for $150.) Besides the fact that I had bet my figurative farm on buying the book in order to write the review—I didn’t even know to ask for review copies back then!—in those pre-Modernist Cuisine days, $250 seemed to me a truly ludicrous ask. Still does, although I have good news for my 2008 self: In 2009, Bloomsbury took the “Big” out of the title and printed a more diminutive edition, available for $60.

Nevertheless, I was smitten: this was a cookbook as art and literature both, with (literally) heady illustrations by artist Dave McKean and engrossing prose by Blumenthal, a chef with a three Michelin-starred restaurant in rural England, who had taught himself to cook by (wait for it) reading cookbooks. The genre I fell in love with reading Joy of Cooking and began to take seriously with Masters of American Cookery was continuing to evolve and change and grow, and I had figured out a way to be a part of that world.

These three books wouldn’t necessarily make my favorite or most-used cookbooks list—that list would be much closer to the set of vegetable cookbooks I wrote about back in April. (The Fussell isn’t even a cookbook!) And they are not without their flaws—the most recent edition of Joy of Cooking is much more approachable and joyful than the 1997 edition, and I’d like to think that had Fussell written her exploration of American food letters today it might feature a more diverse roster of authors. But these books made me who I am, and I wouldn’t be writing this newsletter without them.

In case you missed Tuesday’s issue: A signed Salvador Dalí cookbook shows up on Pawn Stars! A cookbook you literally plant in the dirt and herbs will grow out of it! A Hannah Glasse impersonator! A TV show about 19th century cookbook authors in London! And much more! Become a paid subscriber to read:

I couldn’t find this essay online, but it is included in Fussell’s book of collected essays, Eat, Live, Love, Die.

I remain eternally grateful that the first cookbook I bought as a working single was Mark Bittman’s 1998 (original) edition of How To Cook Everything. Still have even though the binding is shot in multiple places. I feel about that book as you do with your precious ‘97 Joy of Cooking.